George Orwell’s ambivalent relationship with his Anglo-Indian heritage is mostly discussed in the context of critiquing his writing set in Burma or when considering why he joined the Indian Imperial Police as a teenager (and his resignation five years later). Burmese Days, his ‘crisp, fierce, and almost boisterous attack on the Anglo-Indian’; The Road to Wigan Pier, an autobiographical analysis of class and empire; and the narrative essays, ‘A Hanging’ and ‘Shooting an Elephant’, with their subtle, evocative critiques of the impact of British imperialism on the individual are key texts. However, a more contextually nuanced understanding of the depth and breadth of Orwell’s Anglo-Indian cultural identity on his work emerges from applying a prosopographic [1] lens to his social environment and considering less often read novels, essays and reviews. Appreciating his family context assists in re-evaluating how profoundly the values of Anglo-Indian life influenced his outlook and writing. Orwell, as more than one friend commented, although a genuine rebel was ‘more than half in love with what he was rebelling against’.

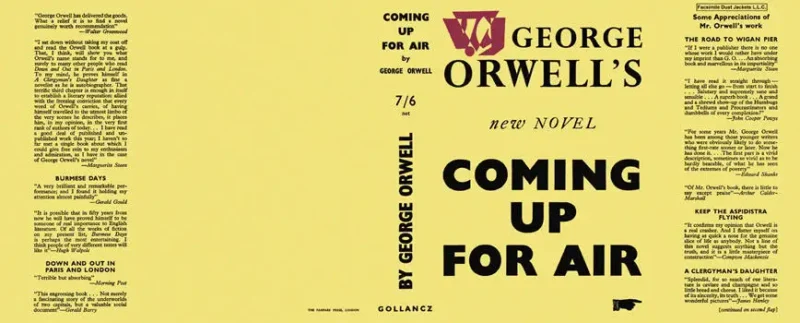

The dust jackets protecting first editions of Orwell’s books quote contemporary responses to his work and include biographical details which place him culturally as an Anglo-Indian. The first American edition of Animal Farm describes the author as being ‘born in Bengal of an Anglo-Indian family; The Lion and the Unicorn emphasises that ‘GEORGE ORWELL was born in 1903 into an Anglo-lndian family’ and that Burmese Days is considered ‘one of the few outstanding novels of Anglo-Indian life’. The first edition of that early novel has a lengthy synopsis on the cover:

Here at last is a cynical, sometimes brutal but immensely entertaining answer to the Rudyard Kipling “white man’s burden” school of novelists – a caustic portrait of the white man in the East as he really is. In this contemporary picture George Orwell draws a number of astonishingly real characters – EIIis, who loathes all natives and longs for the good old days when you could punish your servant with fifty lashes; Flory, cowardly, sensitive, who really likes natives and is therefore unpopular with the whites; Elizabeth Lackerston (sic), pretty, blond and selfish, who has come out to get a husband; U Po Kyin, the enormously fat, naïve native magistrate whose overweening ambition it is to be admitted to the white man’s club. George Orwell knows them all, from their hair to their shoes, and when he is through with them you have a completely convincing picture of the pukka sahib in his adopted home.

The term ‘Anglo-Indian’ has a complex etymology but simply put refers historically to two distinct groups: those of mixed European and Indian ancestry or people of British descent who lived and worked in India. Orwell’s family belonged to the latter category, although he also had Eurasian relatives whom he likely met while stationed in Moulmein. Orwell rarely used the term in reference to a person who had mixed ancestry. However, as seen in a letter to the Royal Literary Fund, while employed at the BBC Eastern Service, Orwell wrote supportively of another colleague who was of ‘Anglo-Indian blood’:

I understand that the Anglo-Indian writer, Cedric Dover, is applying to the Royal Literary Fund for a grant. I believe that he is in some distress through having been unexpectedly called up for service in the Armed Forces. It may perhaps be useful to you if I give you some particulars about him and his work. Cedric Dover has done a good many broadcasts in English for the Indian Section of the B.B.C. besides some for the Hindustani programme section. Several of his talks on literary and sociological subjects were of outstanding merit and three of them are being re-printed in a book of broadcasts which Allen and Unwins are publishing in a few months time. Cedric Dover is also author of the well-known book HALF-CASTE and of other books dealing with Asiatic problems. He deserves encouragement, not only as a talented writer but because writers of Anglo-Indian blood are a very great rarity and are in a specially favourable position to illuminate some of the most difficult of present day problems, in particular, the problem of colour.

In the 1911 Census of India, children born of European fathers and Indian mothers and those born of their offspring, were officially designated as Anglo-Indians. Previously, this group had been more commonly referred to as Eurasians, like the characters Samuel and Francis in Burmese Days. The Constitution of India (1949) formally defined the term in Article 366(2):

An Anglo-Indian means a person whose father or any other of whose male progenitors in the male line is or was of European descent but who is domiciled within the territories of India and is or was born within such territory of parents habitually resident therein and not established there for temporary purposes only.

On my recent research trip to India, at a girl’s school in the hill station of Nainital (where Orwell’s parents married) the school captain described her family as living in ‘the old Anglo-Indian manner’. This is a subtly different use of the terminology. She particularly enjoyed 19th century British literature and had ‘royal Rajput blood’ rather than any European ancestry. The school maintained a proud academic tradition which dated back to their foundation in the 19th century. The current pastor of the church where Orwell’s parents married also described himself as an Anglo-Indian. His description aligns with how the constitution defines the term.

ORWELL’S FAMILY

Orwell’s Anglo-Indian heritage is significantly under-appreciated in scholarly titles and biographies of the writer. One exception is Douglas Kerr’s, Orwell and Empire (2022), which emphasises the significance of Orwell’s Anglo-Indian origins in shaping his perspectives on empire and its contradictions:

Orwell is not our contemporary. To approach him as such risks missing much that makes him most specifically himself. Like any other historical figure, to see him clearly involves judging his distance from where we now stand. One thing that makes him foreign to the twenty-first century is his membership of a class which has vanished (as he said it would) from contemporary Britain, but which was crucial to his formation and the way he saw the world. He had both feet in Anglo-India. This may be the part of Orwell’s historical and cultural environment which is most remote from modern readers, and consequently useful to recover. Three-quarters of a century after Indian independence, the Anglo-Indians, of whom Orwell was one, have disappeared from view as completely as the Elizabethan apprentice boys or the London Huguenots.

The novelist Anthony Powell viewed Orwell as, in many ways, ‘a Victorian figure’. However, much closer friends, especially those who knew him before he assumed his famous pseudonym understood the now largely forgotten world of the Victorian and Edwardian era Anglo-Indians was the one Orwell inhabited. In a letter (1947) to the editor of a literary journal, Orwell outlined his background:

My father was an Indian civil servant, and my mother also came of an Anglo-Indian family, with connections especially in Burma. After leaving school I served five years in the Imperial Police in Burma, but the job was totally unsuited to me and I resigned when I came home on leave in 1927. I wanted to be a writer… .

This concise summary of his family background has not been explored sufficiently since his death.

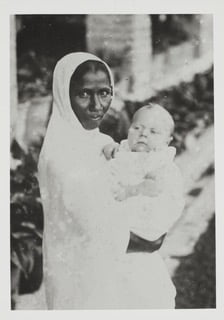

In 1903, Eric Arthur Blair, better known as George Orwell, was born in British India where his father had served in the Opium Department since 1875. His parents, Richard Walmesley Blair and Ida Mabel Limouzin, had married on the 15th June 1897 in Nainital, a popular hill station and important administrative centre. One week after their union, the 78-year-old Queen Victoria, Empress of India, celebrated her Diamond Jubilee. Orwell’s father, his career in the Opium Department emblematic of the economic underpinnings of British imperialism, had been born in 1857, the year of what he would have called ‘The Indian Mutiny’. In 1858, the Government of India Act formally dissolved the East India Company’s rule, transferring sovereign authority directly to the British Crown, inaugurating what came to be known as the British Raj. Although Orwell left India for England with his mother and eldest sister around the age of one, his early childhood and the family’s colonial connections had a lasting impact on his worldview.

Orwell’s ancestors had a long history of military and civil service on the sub-continent during the 19th century. It is telling that a sizeable percentage of his immediate extended family – the Blairs, Hares, Limouzins and Hallileys – were not domiciled in Britain during the year of his birth. His mother’s parents resided in Moulmein, Burma. Blanche Limouzin, Ida’s sister, was working as a teacher when she died ten weeks prior to Orwell’s birth, in Mussoorie, near Nainital. She had been the only relative on either side of the family to attend her sister’s wedding. Born in Moulmein, Blanche went to high school in England with Ida and another sister (the only intellectual in the family, ‘Aunt Nellie’) in the Anglo-Indian enclave of Bedford. Her death must have been a devastating personal loss for Ida. Their youngest brother, who would later become a strong influence in Orwell’s childhood, George Limouzin, was working in Rangoon and would later meet Gandhi in South Africa. Another brother who had been educated in Bedford, Frank Edmond Limouzin, had recently emigrated from Moulmein to South Africa and Joseph Limouzin, an uncle who had worked as a schoolteacher in Bangalore had relocated further south to Yercauld, near Madras.

Richard W. Blair’s brother, Horatio, also employed in the Opium Department (since 1873) was stationed with his wife and children at Hazaribagh, 380 kilometres south of Motihari, where Orwell had been born. Horatio and Richard were the only two of ten children to survive into the twentieth century. All their siblings had died childless by 1884, including Arthur Blair (never mentioned by Orwell’s biographers) who served as District Superintendent in the Indian Imperial Police. Notably, considering Orwell’s own success in navigating civil service examinations nearly four decades later, Arthur passed his ‘police paper’ in 1864 at eighteen years of age. In the year Richard W. Blair joined his two brothers in Bengal, Arthur had been appointed ‘justice of the peace’ and promoted temporarily, although his substantive rank was still that of a District Superintendent (Fourth Grade) to be an additional Deputy Commissioner of Police in Calcutta. In 1877, he was appointed to act as assistant inspector-general of railway police for the Bengal Division after the previous incumbent was suspended from duties. He was making stellar career progress.

On 21 July 1878, Arthur Blair had commenced three months of leave, sailing five days later from Bombay on the Cathay, a P&O Steamship bound for Southampton. The following year, he was granted a furlough but never returned to India, where his two brothers continue serving in the Opium Department into the 20th century. Probate records show the personal estate of this ‘district superintendent of police in the province of Bengal in the East Indies’ was under £450. His mother, also residing at the same address in Bath, was ‘the sole executrix’.

Horatio married, a month after Arthur’s death, on 14 November 1879, to Millicent O’Donnell in Mussoorie. Richard and Horatio (with his wife) return to this same apartment for the next two decades while on leave from the Opium Department. Horatio and Millicent had three children (all born in India) and the 1901 census (taken on 31 March) reveals that one of their daughters, Margaret Rosabel Blair, along with Orwell’s mother and sister, are all residing with Orwell’s paternal grandmother, Frances ‘Fanny’ Blair, in Bath. Their eldest son, Robert Cuthbert Blair (1880-1911), educated the Royal Military College, served with the East Lancashire Regiment in South Africa before transferring to the Indian Army in 1902. He was a captain in the 6th Gurkha Rifles by 1909. He appears to have suicided, throwing himself overboard from a mail steamer in 1911. The remaining four members of the family emigrated to New Zealand before the outbreak of World War One.

Orwell was destined to follow in his father’s and uncles’ footsteps to serve the British empire in India and Burma. Except for Jacintha Buddicom’s testimony that her childhood friend wished to study at the University of Oxford, there is little evidence Orwell wanted to pursue a traditional academic and social path from Eton College to Oxbridge. Buddicom recounted that their family matriarchs were supportive of the idea but Orwell’s father was adamant his son would follow the Blair family footsteps into the ‘Indian civil’. Mr Blair did consult with Andrew Gow, his son’s tutor at Eton, enquiring if a scholarship was possible, only to be told poor academic results made this unrealistic. The ingenuousness of Gow’s advice has been questioned but, either way, Orwell never received a university education and joined the Indian Imperial Police in 1922 as a probationary assistant district superintendent. One school friend, the historian Steven Runciman, recalled Orwell being sentimentally entranced by ‘the allure of the East’ and was not ‘the least bit surprised’ he decided on this option rather than university. Buddicom also understood this was ‘a sort of tradition with his father’s family’ believing it was entirely Mr Blair’s idea and that Eric just ‘fell in with it’. One biographer, finding it challenging to imagine the ‘unassuming’ Mr Blair being ‘adamant’ about anything, surmised it was ‘perfectly reasonable that he would want to stop spending his limited income on educating a son who was old enough to begin a suitable career’. Although his paternal grandfather’s name was Thomas Richard Arthur Blair, it seems likely Orwell’s parents settled on Arthur as a middle name for their only son, rather than the traditional Blair choices – Horatio, Charles, Henry and Thomas – in honour of his uncle who had shown so much potential in the Indian Imperial Police but had died so tragically young. [2]

AMBIVALENCE

Orwell resigned from the Indian Imperial Police in January 1928. In ‘The Autobiography of John Flory’, an early draft (dated loosely c. 1926–1930) of what would become Burmese Days, Orwell romanticises – rather than mocking or criticising – the Anglo-Indian:

My father was rather like myself, only taller, thinner & with more colour in his face. He always had a rather harassed look, except when he was sitting in his library, where my mother seldom penetrated. The atmosphere of this room was quite unlike that of any other room in the house. There were perhaps a thousand books in it, many of them books about Hindu mythology, or about fishing, shooting or travelling in India. I cannot say that I ever read any of these books, but I remember oftening (sic) turning over their pages & looking at strange pictures of people hanging upon hooks, or elephants composed of maidens in extraordinary postures, & wondering vaguely about them in my own mind. I never troubled to enquire their real significance, for the curiosity of children is not very intelligent.

My father used to sit reading these books, with his white shirt open at the neck, smoking cigars from Dindigul. The chairs in the room were of wicker work, such as one finds in India, & there were two faded tiger skins upon the floor. On the walls were old yellow photographs, & a few eastern weapons, among them one or two beautiful dahs captured in the Burma war. I used to look at the handles & scabbards of these dahs, bound with plaited fibres, & speculate dully about the men who used them. The windows were always open, & there was generally a fire in the grate, so that a current of air flowed through the room. And this wind, mingled with cigar smoke, seemed to me like a wind from another land, bearing with it the names of far off dusty places. When I came into the room, & stayed quiet for awhile, my father would talk to me sometimes, & tell me the simple stories of the rubbish that lay about here & there; empty cartridge cases, bad rupees, or dried up peacock feathers. My mother often threatened to “do out” this room, but refrained, probably from mere laziness.

Orwell’s own Burmese ceremonial sword (dah) was one of the few personal items that followed him from Burma to his final residence on Jura. However, this sentimental view was replaced by something more hard-edged in Burmese Days:

Since then he had not even applied for home leave. His father had died, then his mother, and his sisters, disagreeable horse-faced women whom he had never liked, had married and he had almost lost touch with them. He had no tie with Europe now, except the tie of books. For he had realised that merely to go back to England was no remedy for loneliness; he had grasped the special nature of the hell that is reserved for Anglo-Indians. Ah, those poor prosing old wrecks in Bath and Cheltenham! Those tomb-like boarding-houses with Anglo-Indians littered about in all stages of decomposition, all talking and talking about what happened in Boggleywalah in ’88! Poor devils, they know what it means to have left one’s heart in an alien and hated country. There was, he saw clearly, only one way out. To find someone who would share his life in Burma – but really share it, share his inner, secret life, carry away from Burma the same memories as he carried. Someone who would love Burma as he loved it and hate it as he hated it. Who would help him to live with nothing hidden, nothing unexpressed. Someone who understood him: a friend, that was what it came down to.

In The Road to Wigan Pier (1937), Orwell relates his experience of serving in Burma:

… every Anglo-Indian is haunted by a sense of guilt which he usually conceals as best he can, because there is no freedom of speech, and merely to be overheard making a seditious remark may damage his career. All over India there are Englishmen who secretly loathe the system of which they are part; and just occasionally, when they are quite certain of being in the right company, their hidden bitterness overflows.

Orwell, who was near-fatally wounded during the Spanish Civil War and lucky to escape from the secret police, subsequently wrote his most nostalgic novel, Coming Up For Air (1939). This novel is rarely mentioned when considering Orwell’s Anglo-Indian identity or his family and never with understanding of the influences on his characterisation of Hilda and her parents. The protagonist, George Bowling, analyses his wife’s family (and we can almost hear Orwell chuckling):

Hilda belonged to a class I only knew by hearsay, the poverty-stricken officer class. For generations past her family had been soldiers, sailors, clergymen, Anglo-Indian officials, and that kind of thing. They’d never had any money, but on the other hand none of them had ever done anything that I should recognise as work…

It wasn’t long before Hilda took me home to see her family. I hadn’t known till then that there was a considerable Anglo-Indian colony in Ealing. Talk about discovering a new world! It was quite a revelation to me.

Unlike his protagonist, Orwell was intimately acquainted with lifestyles of the ‘Anglo-Indian colony in Ealing’. Electoral records and census data reveals that Nora Ward (née Limouzin), his mother’s eldest sister, had several addresses in Ealing from 1903, the year Orwell was born in Motihari, India. She mostly lived at 56A Craven Avenue, where other members of the family resided intermittently, including her brother George Limouzin and his wife, Ivy. Aunt Nellie continued to live in the upper of two flats after Nora died until 1950. Knowing his own extended Anglo-Indian family lived in Ealing (and his sister Avril boarded at a public school in the suburb), makes this extended quote from the novel an interesting reflection of his own childhood experiences:

Do you know these Anglo-Indian families? It’s almost impossible, when you get inside these people’s houses, to remember that out in the street it’s England and the twentieth century. As soon as you set foot inside the front door you’re in India in the eighties. You know the kind of atmosphere. The carved teak furniture, the brass trays, the dusty tiger-skulls on the wall, the Trichinopoly cigars, the red-hot pickles, the yellow photographs of chaps in sun-helmets, the Hindustani words that you’re expected to know the meaning of, the everlasting anecdotes about tiger-shoots and what Smith said to Jones in Poona in ’87. It’s a sort of little world of their own that they’ve created, like a kind of cyst. To me, of course, it was all quite new and in some ways rather interesting. Old Vincent, Hilda’s father, had been not only in India but also in some even more outlandish place, Borneo or Sarawak, I forget which. He was the usual type, completely bald, almost invisible behind his moustache, and full of stories about cobras and cummerbunds and what the district collector said in ’93. Hilda’s mother was so colourless that she was just like one of the faded photos on the wall. There was also a son, Harold, who had some official job in Ceylon and was home on leave at the time when I first met Hilda. They had a little dark house in one of those buried back-streets that exist in Ealing. It smelt perpetually of Trichinopoly cigars and it was so full of spears, blow-pipes, brass ornaments, and the heads of wild animals that you could hardly move about in it.

However, it is one-dimensional to view the writer as reflexively sneering ‘at Anglo-Indian colonels in boarding houses’. Orwell’s ambivalence towards Anglo-Indians is best understood by examining his attitude to Rudyard Kipling; indeed, he wrote two essays with the title, ‘Rudyard Kipling’. The first, as an obituary in the year of the writer’s death (1936); the second, in response to A Choice of Kipling’s Verse by T.S. Eliot. Both explore his ambivalent feelings about the author, poet and journalist who was a ‘household god’ to families like his own:

In the average middle-class family before the War, especially in Anglo-Indian families, he had a prestige that is not even approached by any writer of to-day. He was a sort of household god with whom one grew up and whom one took for granted whether one liked him or whether one did not. For my own part I worshipped Kipling at thirteen, loathed him at seventeen, enjoyed him at twenty, despised him at twenty-five and now again rather admire him. The one thing that was never possible, if one had read him at all, was to forget him.

The nineteenth-century Anglo-Indians, to name the least sympathetic of his idols, were at any rate people who did things. It may be that all that they did was evil, but they changed the face of the earth (it is instructive to look at a map of Asia and compare the railway system of India with that of the surrounding countries), whereas they could have achieved nothing, could not have maintained themselves in power for a single week, if the normal Anglo-Indian outlook had been that of, say, E. M. Forster. Tawdry and shallow though it is, Kipling’s is the only literary picture that we possess of nineteenth-century Anglo-India, and he could only make it because he was just coarse enough to be able to exist and keep his mouth shut in clubs and regimental messes. But he did not greatly resemble the people he admired. I know from several private sources that many of the Anglo-Indians who were Kipling’s contemporaries did not like or approve of him. They said, no doubt truly, that he knew nothing about India, and on the other hand, he was from their point of view too much of a highbrow. While in India he tended to mix with “the wrong” people, and because of his dark complexion he was wrongly suspected of having a streak of Asiatic blood. Much in his development is traceable to his having been born in India and having left school early. With a slightly different background he might have been a good novelist or a superlative writer of music-hall songs.

These passages contain many of the themes which interested Orwell and appear in his writing from the earliest drafts made as a budding author through to his final reviews and notes for a novella. It is instructive that he rather admired Kipling in 1936 after ‘despising him’ while serving in Burma. The ‘private sources’ may have been from his own service with the Indian Imperial Police; his parents, their friends and other relatives; or possibly colleagues and friends at the BBC Eastern Service, where he worked for two years as a Talks Assistant, then producer. During this period working for the BBC, he was loyal, encouraging and supportive of colleagues, especially Mulk Raj Anand, who shared many of his ideological concerns.

A COMPLEX INHERITANCE

Orwell was always drawn to the sub-continent and there are many clues to the fundamental importance of this Anglo-Indian heritage to his identity. In 1938, he considered working on the Pioneer, a newspaper that had employed Kipling. Towards the end of World War Two, while working as a war correspondent in Europe, he wrote to the editor of the Observer, David Astor, suggesting that he travel to Burma to ‘report the closing stages of the campaign and interview some of the political leaders’. He was in favour of the country gaining ‘Dominion status’:

… it would be a good solution for the country, giving them a chance of development without cutting the tie with Britain.

The fact that at the end of his life Orwell was drafting A Smoking Room Story – ‘a nouvelle of 30,000 to 40,000 words’ which he intended to be ‘a novel of character rather than of ideas, with Burma as background’ – indicates the sub-continent was never far from his mind. He reviewed India Called Them by Lord Beveridge, describing it as ‘a picture of British India in the forgotten decades between the Mutiny and Kipling’s Plain Tales from the Hills’:

… the period covered by his career, 1858–1893, was a bad period in Indian-British relations. Among the British, imperialist sentiment was stiffening and an arrogant attitude towards “natives” was becoming obligatory. The greatest single cause was probably the cutting of the Suez Canal. As soon as the journey from England became quick and easy the number of Englishwomen in India greatly increased, and for the first time the Europeans were able to form themselves into an exclusive “all white” society. On the other side the Nationalist movement was beginning to gather bitterness. Henry Beveridge supported unpopular reforms, wrote indiscreet magazine articles, and in general stamped himself as a man of dangerous views. As a result he was repeatedly passed over for promotion and spent most of his career in subordinate jobs on fever-stricken islands of the Ganges delta.

Orwell’s ongoing fascination and insight into the period is evident throughout the review and he mentions enjoying the ‘good photographs’. His droll sense of humour is on display when considering ‘the exact composition of an Anglo-Indian household in the ’eighties’ and ‘why it was necessary for the Beveridges – a couple with three children, living very modestly by European standards – to have thirty-nine servants’.

Re-examining Orwell’s life, through the prism of his Anglo-Indian inheritance, reveals rich, interwoven familial threads. In early December 1949, Orwell’s Aunt Nellie wrote to an Esperantist friend concerned that ‘Eriko’ was too unwell to make the trip to Switzerland with his new wife. Orwell was intending to convalesce at a Swiss sanatorium in a last-ditch attempt to treat the pulmonary tuberculosis which threatened his life. What is particularly interesting about this letter is that Limouzin, unlike many of Orwell’s friends and family, wholeheartedly approved of the ‘very intelligent’ Sonia Brownell as ‘certainly a most suitable companion for Eric’. Undoubtedly, Nellie would have met Sonia at the hospital in University College London where Orwell was eventually to die. Brownell, whom he married in October 1949, another Anglo-Indian was born near Calcutta, at Ranchi. Orwell’s father served during the First World War with the 51st Ranchi Pioneers, an Indian Labour Corps company.

While Orwell grew up in England, his father remained in India until his retirement nearly a decade after his son’s birth, reinforcing a sense of familial estrangement and the detachment often felt by children of colonial officials. This separation from his father, coupled with his family’s limited financial means, shaped Orwell’s awareness of class disparities and the peculiarities of Anglo-Indian social identity. His admission, in ‘Why I Write’, about an inability to ‘abandon the world-view … acquired in childhood’ provides an important insight into his personality. It also aligns with what Sir Richard Rees – Orwell’s friend, editor, literary executor and another Anglo-Indian – believed, that to understand Orwell, one must understand Blair.

Eric Blair was raised and educated to be a servant of empire. Although they were British by blood, Anglo-Indians of Orwell’s class occupied an ambiguous social space, privileged relative to indigenous Indians but often less affluent or influential than their compatriots in Britain. This complex sense of identity made him an acute observer of cultural, racial and political tensions able to describe the contradictions of empire with a clarity that eluded contemporaries. His childhood friend and editor of Horizon, Cyril Connolly, reviewed Burmese Days hoping the novel, its ‘irony tempered with vitriol’ would ‘find its way to the club at Kyauktada’. Orwell, although he became an ideological dissenter, effectively critiquing British imperialism, never completely escaped his ‘Anglo-Indian patrimony and prejudices’. Orwell famously distrusted left-wing intellectuals whose loyalty lay with the Soviet Union, like any other member of the class he was born into.

Orwell’s personal essays provide some of his most direct and incisive critiques of empire. In ‘Shooting an Elephant’ (1936), he recounts an incident during his time in Burma that encapsulates the moral dilemmas of colonial rule. The narrator, a British officer, feels compelled to shoot an elephant to maintain his authority in front of a local crowd, despite his personal reluctance. This essay reveals Orwell’s recognition of the performative nature of colonial power and the ways in which the oppressors are themselves trapped by the expectations of the system they enforce. Other essays, such as ‘A Hanging’ (1931), explore his revulsion at the dehumanising effects of imperialism. Both essays draw on Orwell’s personal experiences in Burma. In Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), Orwell’s critiques of totalitarianism can also be read as indirect reflections on the authoritarianism inherent in imperial governance. While these works are not explicitly about colonialism, their exploration of power, oppression, and ideological control resonates with Orwell’s earlier reflections on empire. The hierarchical structures depicted in these novels – whether the stratified society in Oceania or the class distinctions among the animals in Animal Farm – echo the rigid social stratifications of colonial India.

Orwell was both a product of the imperial system and a dissenter from its ideology. His Anglo-Indian ancestry and family upbringing were formative influences on his writing, shaping his critiques of empire, class, and power. His essays, in particular, reveal the ways in which his personal experiences as an Anglo-Indian and a colonial officer informed his understanding of empire’s contradictions. Orwell, always a complex and paradoxical figure ‘more than half in love with what he was rebelling against’ recognised that it was ‘very difficult to escape’ culturally from the ‘class into which you have been born’.

[1] See Lawrence Stone: ‘Prosopography’, Daedalus, Volume 100, Number 1, 1971, pp. 46–79.

[2] It is an odd historical irony that Orwell was also a District Superintendent of Police and died of pulmonary tuberculosis (phthisis) like his Uncle Arthur.

REFERENCES

Ancestry.com (2018) UK, Registers of Employees of the East India Company and the India Office, 1746-1939

Blair, E.A., ‘Comment on exploite un people. — L’Empire britannique en Birmanie’, Le Progrès Civique, No. 507, 4th May 1929

Blunt, Alison (2011) Domicile and Diaspora: Anglo-Indian Women and the Spatial Politics of Home, Wiley-Blackwell

Bowker, Gordon (2004 [2003]) George Orwell, London: Abacus

Buddicom, Jacintha (2006 [1974]) Eric and Us, Finlay Publishers, postscript edition

Buettner, Elizabeth (2004) Empire families: Britons and Late Imperial India, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press

Connolly, Cyril (1949 [1938]) Enemies of Promise, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.

Connolly, Cyril (1935) ‘Review: Burmese Days’, The New Statesman and Nation, 6 July

Coppard, Audrey and Crick, Bernard (1984) Orwell Remembered, London: Ariel Books/BBC

Crick, Bernard (1992 [1980]) George Orwell: A Life, Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, second edition

Davison, Peter (2013) George Orwell: A Life in Letters, New York: Liveright

Fyvel, T.R. (1982) George Orwell: A Personal Memoir, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson

General Register Office (1879) Death Certificate for Arthur Blair, Registrar’s District of Bath, Registrar’s Sub-District of Walcot, County of Somerset, Entry No. 20

Keeble, Richard, ‘Letters from Paris Throw New Insights on Orwell’, George Orwell Studies (2022) Vol. 6, No. 2 pp. 3-7

Kerr, Douglas (2022) Orwell and Empire, Oxford University Press

Limouzin, Nellie (1949) Letter: E.K.L. to Lucien Bannier, 5 December 1949, Paris: SAT Archive

London Gazette (1909) 26 March

London Gazette (1911) 15 September

London Gazette (1917) 8 October

Madras Weekly Mail, 26 March, 1903

Moore, Darcy, ‘The Two Arthurs’, George Orwell Studies, (2024a) Vol. 9, No. 1 pp. 135-144

Moore, Darcy, ‘Orwell and Bedford’, History in Bedfordshire, (2024b) Vol. 10, No. 5, Summer pp. 5-15

Moore, Darcy, ‘Peter Duby (1946-2023)’, The Orwell Society Journal, (2024c) March, No. 23 pp. 45-48

Moore, Darcy, “BBC transcript found: ‘The meaning of scorched earth’”, George Orwell Studies (2024d) Vol. 8, No. 2 pp. 20-31

Moore, Darcy, ‘Orwell in Cornwall’, George Orwell Studies (2023) Vol. 8, No. 1 pp. 142-158

Moore, Darcy, ‘Orwell and the Secret Intelligence Service’, George Orwell Studies (2022a) Vol. 6, No. 2 pp. 9-16

Moore, Darcy, ‘Orwell and Empire by Douglas Kerr’, George Orwell Studies (2022b) Vol. 7, No.1 pp. 102–106

Moore, Darcy, ‘Orwell in Burma: The Two Erics’, George Orwell Studies (2021) Vol. 5, No. 2 pp. 6-24

Moore, Darcy, ‘Orwell’s Aunt Nellie’, George Orwell Studies (2020) Vol. 4, No.2 pp. 30-44

Muthiah, S; MacLure, Harry (2014) The Anglo-Indians: A 500-Year History, Niyogi Books: Kindle Edition

Orwell, George (1934) Burmese Days, New York: Harper and Brothers

Orwell, George (1941) The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius, Searchlight Books No. 1, London: Secker and Warburg

Orwell, George (1946) Animal Farm, New York: Harcourt and Brace

Orwell, George (1997 [1934]) Burmese Days, The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. II, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1997 [1936]) Keep the Aspidistra Flying, The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. IV, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1997 [1937]) The Road to Wigan Pier, The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. V, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1997 [1939]) Coming Up For Air, The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. VII, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1997 [1945]) Animal Farm, The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. VIII, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1997 [1949]) Nineteen Eighty-Four, The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. IX, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1998 [1903-1936]) A Kind of Compulsion: The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. X, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1998 [1937-1938]) Facing Unpleasant Facts: The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. XI, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1998 [1941-1942]) All Propaganda Is Lies: The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. XIII, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1998 [1943]) Two Wasted Years: The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. XV, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1998 [1943-1944]) I Have Tried to Tell the Truth: The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. XVI, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1998 [1945]) I Belong to the Left: The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. XVII, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1998 [1946]) Smothered Under Journalism: The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. XVIII, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1998 [1947-1948]) It Is What I Think: The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. XIX, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1998 [1949-1950]) Our Job Is to Make Life Worth Living: The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. XX, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (2006) The Lost Orwell: Being a Supplement to the Complete Works of George Orwell, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Timewell Press

Rees, Richard (1961) Fugitive from the Camp of Victory, London: Secker & Warburg

Shelden, Michael (1991) Orwell: The Authorised Biography, London: Heinemann

Taylor, D.J. (2023) Orwell: The New Life, London: Constable

Spurling, Hilary (2002) The Girl from the Fiction Department: A Portrait of Sonia Orwell, London: Hamish Hamilton

Stansky, Peter and Abrahams, William (1972) The Unknown Orwell, New York: Alfred A. Knopf

Starling, John; Lee, Ivor (2009) No Labour, No Battle: Military Labour during the First World War, Stroud: Spellmount

Thacker, Spink & Co. (1903) Thacker’s Directory, Calcutta: Thacker, Spink & Co.

Wadhams, Stephen (1984) Remembering Orwell, Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin

Discover more from Darcy Moore

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Ronald Binns

Another terrific short essay!

Your thesis that the Anglo-Indian dimension to Orwell and his work is crucial both biographically and critically is very persuasive. Arthur Blair is plainly an important discovery regarding the origin of Eric Blair’s middle name as well as in understanding his career as a colonial police officer.

Your suggestion that there is a colonial sub-text to Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four is refreshingly original and I hope you will develop this at greater length on another occasion.

Darcy Moore

Thanks Ronald. You always take the time to read and comment on my ideas. It is very highly appreciated! I intend to dig more deeply into RW, Horatio and Arthur’s experiences in India on my next visit. I need to re-read both texts (again) to see if this a colonial bridge too far. I am confident that such a reading of Nineteen Eighty-Four will prove fruitful. Darcy

Douglas Kerr

Well done Darcy, another very useful contribution to filling out the Orwell story. We are once again on the same page! your insistence on the importance of O’s Anglo-Indian identity and history following several of the same tracks as ORWELL AND EMPIRE. The prosopographical approach is interesting. What would be good to see now – now that they have virtually disappeared – would be a good solid social and cultural history of the Anglo-Indians, not another Raj book but one that looked closely at what they did, where they lived, what they thought and what people thought of them, when they were back in the “home country”.

They are usually portrayed, by Orwell among others, as rather sad, superannuated, nostalgic, reactionary boffers, as no doubt many of them were. Did they have anything contribute to the country to which they had returned? The older ones must have found it baffling. How did they get on with their own children, who may have had very different ideas about the empire they had served? The Blair family is an interesting example, particularly the relation between Eric and his father. But quite a large proportion of Orwell’s friends of his own generation came from Anglo-Indian homes and histories. Kipling, I think, doesn’t have much to say about Anglo-Indian returnees, of whom he himself was one. Who does? Paul Scott, perhaps. Jane Gardam (in OLD FILTH). Others?

Darcy Moore

Thanks Douglas. For a while my interest in Orwell’s ancestors may have seemed to some as not really that relevant to understanding more about the writer’s work. However, I am hoping that a barrage of posts (esp. re: ACD and his grandfather) reveal how much more Orwell knew and referenced his extended family in his work. Now that I know Avril boarded at a school in Ealing Broadway (and the many maternal relatives who lived in this Anglo-Indian enclave) it makes me enjoy his jibes in CUA even more. I will return to India later this year and do more research, specially on RW, Horation and Arthur Blair’s service.

In answer to your question, it appears the Anglo-Indians as a class did quite incredibly brilliant things on the sub-continent – administrative, intellectually and in an engineering sense – but there are not too many back in the “home country” that have drawn my attention. Two books I referenced, Blunt (2011) and Buettner (2004) have a little to say on the matter. Look back to the Orwell’s Window post and check our Richard Rees’s father too. He became and MP. I would draw your attention to the following work, if you do not know it:

Dewling, Clive (1993) Anglo-Indian Attitudes: The Mind of the Indian Civil Service, London: The Hambledon Press

BTW I have located the Lady Mary portrait and have oral history suggesting Orwell had it above his various writing desks.