“She was the mistress of a peer of the Realm for over thirty years but would not marry him when the subject was raised because his intellect was not, apparently, equal to his sex drive.” Eric & Us (2006)

Eric Blair, better known by his pen-name George Orwell, proposed marriage on more than one occasion to his childhood companion, Jacintha Buddicom. She refused him but many years later, in a letter to a relative, regretted not being ready for “betrothal” as “Eric was less imperfect than anyone else I ever met”.

There is much more to the story.

Buddicom published Eric & Us: A Remembrance of George Orwell nearly fifty years ago. Her book detailed the close companionship she and her siblings had shared with the young Eric Blair. It concealed important information and when Dione Venables, Buddicom’s cousin and literary executor, re-issued Eric & Us (2006) she included a postscript containing several revelations.

One of the lesser of these, that Buddicom had a long-term affair with an un-named peer of the Realm, is deserving of further examination considering the invisible web of interpersonal networks and thematic importance of social class in Orwell’s writing.

“The lower-upper-middle class”

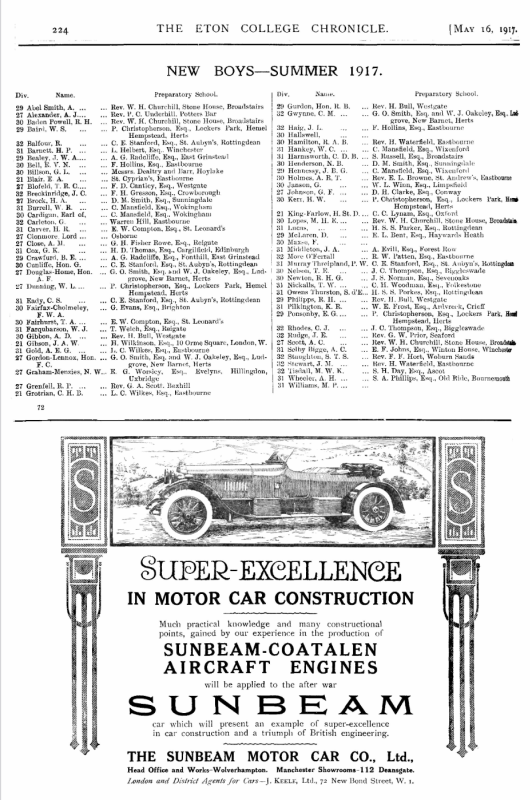

Orwell commenced his education at Eton College in the summer of 1917. He was one of the intellectual elite, a King’s Scholar (KS), at a school which educated the British ruling class and dated back to the fifteenth century. He was very conscious of only being able to attend this institution with a scholarship and later wrote about becoming “an odious little snob” as a result of the experience:

“At school I was in a difficult position, for I was among boys who, for the most part, were much richer than myself, and I only went to an expensive public school because I happened to win a scholarship. This is the common experience of boys of the lower-upper-middle class, the sons of clergymen, Anglo-Indian officials, etc., and the effects it had on me were probably the usual ones. On the one hand it made me cling tighter than ever to my gentility; on the other hand it filled me with resentment against the boys whose parents were richer than mine and who took care to let me know it. I despised anyone who was not describable as a “gentleman,” but also I hated the hoggishly rich, especially those who had grown rich too recently. The correct and elegant thing, I felt, was to be of gentle birth but to have no money. This is part of the credo of the lower-upper-middle class.” The Road to Wigan Pier

In an odd coincidence, that “peer of the Realm”, Jacintha Buddicom’s long-term lover, commenced his schooling at Eton with Orwell. Half-a-dozen names from E.A. Blair, on the list of new boys who arrived as a generation were slaughtered on the western front, was Chandos Sydney Cedric Brudenell-Bruce. Convention dictated he be addressed as the Earl of Cardigan, a courtesy title employed prior to becoming Marquess of Ailesbury on the death of his father.

This is an unexpected story of strangely perpendicular, parallel lives. Like Orwell, Cardigan looked back fondly on his Edwardian childhood:

“I was born in the reign of King Edward VII and, ever since, I have toyed with the notion that this brief reign was the happiest in English history. There are grounds for so thinking; for Edwardian England was a land of security, of continuity and (for the average man) of gradually growing prosperity (from Setting My Watch By The Sundial, 1970)

He remembered the death of King Edward VII (and an inglorious ancestor) in his memoir published sixty years after the funeral:

“.… alas, good King Edward was destined to die in the year 1910. My final memory is of his funeral; for we were invited lo London by a person then known to me as “”the old lady””, whose house in Park Lane overlooked the route of the impending funeral procession. She was in fact Adeline, Countess of Cardigan, whose husband (being our distant cousin) had gained immortality by his leadership of the Light Brigade at Balaclava.” (ibid)

A photograph of Cardigan’s parents taken for the coronation of George V the following year highlights their elevated social status.

Orwell’s parents were “lower-upper-middle class” but boasted a grander ancestry built on the profits of slavery. In the mid-18th century Orwell’s ancestors had been wealthy enough to commission Sir Joshua Reynolds to spend five years completing a portrait celebrating their status and privilege. Those days ended with the cessation of slavery. Orwell’s father, the tenth and youngest child in his family, retired on a modest government pension in 1912.

In his memoir, Setting My Watch By The Sundial, Brudenell-Bruce illustrates the extreme social snobbery of his own family in a chapter titled, Of “High Society”:

“I had an Oxford friend who, being my senior by a year or two, had served in the Navy during the late years of the Kaiser war. And – though he would seldom speak of it – he had on one occasion shown such gallantry that the Albert Medal (that rare decoration) had been awarded to him.

To me, an admirable and an interesting young man; but how could I have introduced him into our family circle? My mother might well have enquired as to where his family’s estate was situated: the reply would have been that his father was a village schoolmaster in a remote part of Wales – and this could have brought conversation to a grinding halt!” (from Setting My Watch By The Sundial, 1970, p. 23)

Cardigan was a full fee paying Oppidan between 1917 and 1922. Blair departed Eton in 1921, attending a cramming school in preparation for the Indian Civil Service exams. By late 1922 he was serving in Burma, with the Indian Imperial Police, one of the least desirable postings in the British empire. Cardigan attended the University of Oxford where he became friends with Prosper Buddicom, Jacintha’s brother.

Social class is an important concept in Orwell’s writing and life story. The Eton Register, published the year before Eric Blair assumed his famous pseudonym in 1933, contrasts their status.

In 1933 – an era when all one needed to take a flight anywhere (fuel would permit) was the wealth to buy a plane and an empty field – Cardigan published Amateur Pilot, a guide to flying. Orwell published Down and Out in Paris and London.

The Earl of Cardigan

While Orwell was in Burma, Cardigan secretly married Joan Houlton Salter (1904-1937) on 5th July 1924 in a registry office in Brentford. The news was reported nearly 12 months later and corresponds with the young aristocrat fleeing his life at Oxford.

After the press broke the scandal, Cardigan telegrammed Christ Church College apologetically and his father subsequently wrote requesting his son be shown some leniency considering the delicate situation.

It was not the first time the Marquess of Ailesbury corresponded with the college authorities regarding Cardigan’s behaviour. In 1924, he received a letter explaining that they had to “send Lord Cardigan down” for the remainder of the term. This was just two months prior to Cardigan’s “secret marriage” and it appears he was burning the candle at both ends.

The married couple went touring the country by car to escape press attention. Subsequently, an attempt to rescue the family reputation was undertaken with a formal wedding ceremony and publicity blitz in the fashion pages of popular magazines. Lieutenant Wilts, his publicist (at least he was c. 1933), provided an essential service for Lord Cardigan and his family.

Motor Journalism

Cardigan fashioned a career where he could pursue his passion for motorcars and aeroplanes. Using his aristocratic title to advantage, advertising and writing reviews of new model cars was to become his routine occupation until World War II intervened:

“Motor journalism, in the nineteen-twenties, could be quite an intriguing occupation for many new and unusual cars were being introduced, and quite commonly one might be given one for a long week-end. Normally, one would be expected to take over the demonstration car at its manufacturers’ London showrooms, i.e. in some main thoroughfare such as, perhaps, Oxford Street. And to take over (for example) a supercharged Mercedes, or a sort not seen in England before, and to drive away faultlessly amidst the rush and roar of London traffic-this called for as much skill as even young Cardigan (that enthusiast) was able to muster.” (from Setting My Watch By The Sundial)

During this period, Brudenell-Bruce wrote reviews in sports publications and published his first book as the Earl of Cardigan. Youth Goes East (1928) chronicled his journey through Europe in a car provided for an advertising campaign.

In 1927, the Morris company had decided to replace their familiar models with more powerful cars thought to have great commercial potential. Cardigan was commissioned to bring a new model to the attention of the motorists of Europe. Accompanied by his wife and her brother Henry, he would drive “Miranda” through Europe seeking out the local Morris agent in each of the countries visited.

In contrast, Orwell, around this time, ended his imperial career in Burma and started going “down and out” in London, then Paris.

Cardigan and Buddicom

Cedric Brudenell-Bruce was “the peer of the Realm” with whom Jacintha Buddicom (known as “Cini” to family and friends) had an affair. The timeline of her relationship with Cardigan is unclear. Brudenell-Bruce married three times. Firstly to Joan Salter (1924-1937); Joyce Quennell (1944-1948) and finally Jean Wilson from 1950 until his death in 1974. Buddicom gave birth to an illegitimate child – fathered by another of her brother’s Oxford friends, Thomas Tunnard-Moore (1904-1984) – in July, 1927.

When did their affair commence? The late 1920s – or before, when they were first introduced by Prosper Buddicom?

Buddicom published a book of poetry in the USA anonymously, The Compleat Workes of Cini Willoughby Dering, in 1929. The book is dedicated to “Colin”, her pseudonym for Cedric. Family sources also believe that Cedric “badgered” Jacintha about marrying and although she refused him, remained quite faithful. If this is correct, her poetry published in 1929 suggests she was already in a relationship with Cardigan shortly after her child was born – or that “Colin” is Tunnard-Moore.

The First Lady Cardigan

Tragically, Brudenell-Bruce and his first wife provided more scandal for the British press in 1937. Lady Cardigan leapt to her death from the seventh floor of the Savoy Hotel in London. The inquest into the tragedy was widely-reported towards the end of July.

Lady Cardigan had decided not to attend a “royal garden party” with her husband and disappeared. The coroner, Justice Ingleby Oddie, described her as “quite demented” during the three-days she spent “wrecking” her hotel room in London. He returned a verdict of “suicide while of unsound mind”.

The Daily Mirror was just one of the many newspapers that reported the tragic story in disturbing detail:

Police-Constable Jackson said he was called to Savoy-way at 8.30 p.m. and saw a woman lying partly on the footway, partly on the roadway, apparently dead. She wore a brown slip a pair of green shoes and a wrap.

Her hand was touching a photograph of a boy about four years old.

Dr Thomas Moreton, a house surgeon of Charing Cross Hospital, gave details of the post-mortem examination.

In the stomach he found a piece of glass about half an inch square. There were extensive injuries to the body. The scalp was cut in two places. The skull had numerous fractures.

Lady Cardigan died as a result of these injuries.

One wonders what was included in the letter Cardigan “very properly” provided the coroner from his late wife? Selective quotes were provided, including that she told her husband he “had nothing to blame” himself for and an understandable wish that her two children were “shielded” from the news. The coroner (and the newspaper articles) relayed that Lady Cardigan’s mother also committed suicide and that she was from a “bad family”.

This had been a truly horrible month and year for Cardigan and his young family. One imagines he was supported by one of his closest friends, Prosper, at this time of terrible sadness and (very public) turmoil. The closeness of the connection with the Buddicoms revealed by the fact that Cedric Brudenell-Bruce was the godfather of Prosper’s own daughter, born on the 27th June, 1937. Lady Jennifer Brown (née Buddicom) explained that her:

“… christening would have been very near the date of Cardigan’s first wife’s suicide. No wonder the only evidence I have that he was my godfather is a christening mug as he played no further part in my life”.

World War II

Cardigan continued to publish car reviews in the late 1930s until his “happy, peacetime adventures” were brought to an end when war was declared (Setting My Watch By The Sundial). Brudenell-Bruce was already a subaltern in the Royal Wiltshire Yeomanry, which one of his “ancestors” had founded but cavalry being worse than useless, quickly organised a transfer to the Berkshire Territorials. His “mechanical knowledge would be of immediate use” looking after 112 vehicles in the “Workshop Platoon” (ibid).

During the “Phoney War” he was based in Northern France. When Dunkirk fell, he became a prisoner of war but escaped back to England via Spain. This was widely-reported in the press and I Walked Alone, recounting these experiences, was published in 1950.

By 1945 he was promoted to Major and returned to Europe to serve in the Allied Military Government in Germany. He was based at Displaced Persons Camps in Bocholt and then Hamminkeln. During this period Orwell was a war correspondent and wrote several newspaper articles on the successes and challenges for the officers working in the Military Government.

More to consider

There are many connections worthy of further exploration that link Orwell and Cardigan’s social networks, some quite invisible.

Brudenell-Bruce’s second wife was Joyce Frances Warwick-Evans Quennell (1917-2000) who he married in 1944. She was born too late to be one of the “Bright Young Things” but had previously been married to Peter Quennell and knew how to party. In a strange quirk of fate, Joyce attended St Felix’s, a boarding school in Southwold, where she was taught by Brenda Salkeld, Orwell’s friend, sort-of-girlfriend and correspondent for nearly twenty years (Taylor).

Cyril Connolly, Orwell’s school-friend and editor at Horizon, reported that Peter Quennell had been “v. enthusiastic” about Homage to Catalonia (1938)

Called “Glur” by Quennell (her stepfather’s surname) he also coined “The Lost Girls” to describe the “adventurous young women who flitted around London, alighting briefly here and there, and making the best of any random perch on which they happened to descend” (Taylor). This designation included Orwell’s second wife, Sonia Brownell (1918-1980) who was a member of this social set which intersected with many people Orwell knew. He originally met her via Connolly at the Horizon office.

Lord and Lady Cardigan divorced in 1948. Glur’s “indiscretions with the American soldiers billeted in a wing of the house caught the eye of her husband’s servants. When the divorce petition came to court, the Earl’s butler was called to give evidence” (ibid).

The 7th Marquess of Ailesbury

The family seat, Tottenham House in Savernake Forest, Wiltshire, was vacated just after the war and became a school. Savernake Forest had been established as a royal forest sometime after the Norman Conquest and reached its greatest extent around 1200 when it extended to some two hundred and sixty square kilometres of land (Lennon). This ancestral home was often featured in the social pages of popular magazines.

In 1961, Brudenell-Bruce became the Marquess of Ailesbury. His titles included: Baron Bruce of Tottenham; Baron Brudenell of Stonton; Earl Bruce of Whorlton; Lord Ailesbury; Earl of Ailesbury; and, Viscount Savernake. He wrote two books under the name Ailesbury: The History of Savernake Forest (1962); and a memoir which studiously avoided controversial aspects of his life, Setting My Watch by the Sundial (1970).

In the final chapters of his memoir, Lord Ailesbury ruminates against the creeping socialism which has made it impossible for those with inherited wealth to maintain their lifestyles. He discusses his voting record, membership of the “Association of Conservative and Unionist Peers” (which supported apartheid South Africa and fiercely opposed non-white immigration to Britain). He admired the hardline imperialist, Lord Salisbury (for his support of white rule in Rhodesia and other colonies).

Brudenell-Bruce, who described himself as “a backwoodsman”, only made one speech in the House of Lords between 1961-1974. Possibly this was because he departed England to avoid taxes. The speech, on immigration, although dressed-up in the rhetoric of serving the interests of “the ordinary British citizen” reveals his politics to be the polar opposite of Orwell’s:

“To my mind that duty comes first; and if one is able to accept that, then I would say that where duty is plain, surely a non-problem results. I should like to suggest that this matter of immigration is a statistical non-problem. So it seems to me that what is needed to deal with this matter is something in the nature of a Civil Service working party (more effective, perhaps, than any that now exist) which I should like to see headed by a non-politician, by a man of eminence, if possible a man of eminence in the business world, who is known for his ability to sort out problems and produce the right answers.” (3 November, 1966)

Brudenell-Bruce always followed his father’s advice to “vote against the Bishops” in the House of Lords. He proudly recounted how he did just this in favour of capital punishment and also demonstrated a refusal to be “beastly” towards the Rhodesians.

Jacintha Buddicom had noted that his “intellect” was not as advanced as his other drives.

In Conclusion

In 2006 Dione Venables, Buddicom’s cousin and literary executor, re-issued Eric & Us with a postscript revealing the affair with the un-named “peer of the Realm” and that Orwell had attempted to sexually assault Jacintha in September 1921. It is a complex story which in many ways is still unfolding as the secrets, gaps and silences are examined more thoroughly and further consideration given to the period from 1921-1930 in Orwell’s life.

Orwell and Cardigan both wished to marry Jacintha Buddicom. She rejected their proposals and never married! There is much more to uncover, especially about the period from July 1927-June 1928 that is significant to understanding Eric Blair’s motivations to become the kind of writer we know as Orwell.

Chandos Sydney Cedric Brudenell-Bruce has now been identified and some surprising connections to Orwell revealed.

Acknowledgments

My appreciation for Dione Venables’ endless patience, responding to emails and answering questions, cannot be understated. It was to Dione I turned when needing help with The Compleat Workes of Cini Willoughby Dering. I am also extremely grateful to Melanie Scott for contacting me to discuss what she knew about her grandmother and to Jennifer Brown, Jacintha’s niece, whose responses to my questions provided an invaluable piece of the jigsaw.

Archivists who are willing to genuinely assist with research challenges make a huge difference, especially when those documents have not been digitised. Warm thanks are due to Judith Curthoys, Georgina Robinson and Stephie Coane.

FEATURED IMAGES: courtesy of Orwell Archive and National Portrait Gallery

REFERENCES

Aberdeen Press and Journal, 28 May 1928

Ailesbury, George, Marquess of, Letter to Christ Church College, 16 May, 1924

Ailesbury, George, Marquess of, Letter to Christ Church College, 1 May, 1925

Ailesbury, Cedric, Marquess of, Setting My Watch By The Sundial, Wiltshire: Charles H. Woodward, 1970

Belfast News-Letter, 29 April, 1925

Birmingham Daily Gazette, 30 April, 1925

Birmingham Gazette, 26 July, 1937

Britannia and Eve, Vol. 16, No. 1, January 1938

Buddicom, Jacintha, The Compleat Workes of Cini Willoughby Dering, New York: Payson & Clarke, 1929 (published anonymously)

Buddicom, Jacintha, Eric & Us: A Remembrance of George Orwell, Frewin, 1974

Buddicom, Jacintha & Venables, Dione, Eric & Us: The Postscript Edition, Finlay, 2006

Cardigan, The Earl of, Telegram, 29 April, 1925

Cardigan, The Earl of, Youth Goes East, London: Eveleigh Nash and Grayson, 1928

Cardigan, The Earl of, Amateur Pilot, London: Putnam, 1933

Cardigan, The Earl of, The Wardens of Savernake Forest, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1949

Cardigan, The Earl of, The Life and Loyalties of Thomas Bruce, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1950

Cardigan, The Earl of, I Walked Alone, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1951

Courier and Advertiser, 24 April, 1928

Daily Mirror, 24 April 1928

Daily Mirror, 28 July, 1937

Eton College Chronicle, Alphabetical School List for the Summer School-Time 1917, Spottiswoode, Ballantyne & Co Ltd.. Available from: https://archives.etoncollege.com/PDFViewer/web/viewer.html?file=%2fFilename.ashx%3ftableName%3dta_chronicles%26columnName%3dfilename%26recordId%3d742%23page%3d20

The Illustrated London News, 19 July, 1930

Leicester Evening Mail, 27 July, 1937

Lennon, Ben. “A Study of the Trees of Savernake Forest and Tottenham Park, Wiltshire, Using Statistical Analysis of Stem Diameter”, Garden History, 2014

Old Etonian Association, Eton College Register Part VIII 1909 – 1919, W. H. Smith & Son, Ltd., Arden Press, Stamford Street, S.E.I. 1932. Available from: https://archives.etoncollege.com/PDFViewer/web/viewer.html?file=%2fFilename.ashx%3ftableName%3dta_registers%26columnName%3dfilename%26recordId%3d12

Orwell, George, The Road to Wigan Pier, The Complete Works of George Orwell – Volume 5, Secker & Warburg, 1997

Sketch, 15 July, 1925

Sketch, 2 May, 1928

Sketch, 29 May, 1929

Sketch, 11 December, 1940

Sphere, 26 July, 1930

Tatler, 1 March, 1939

Times, 30 November, 1974

Taylor, DJ, Lost Girls: Love, War and Literature: 1939-51, London: Constable, 2019

Western Morning News and Mercury, 29 April, 1925

Graham Rees

A tour de force, sir.

Douglas Kerr

Fascinating. Looks like you’ve hit the jackpot with Cardigan, who seems to be in almost all respects the opposite of Orwell. Poor Jacintha! If Jacintha was his mistress for thirty years, that must have been going on through at least two, perhaps all three of his marriages.

I wonder if he and Orwell ever met, after Eton. I suppose it’s possible, with the Buddicom and Quennell connections.

If Cardigan is ‘Colin’, and she refused to marry him, the Cini poems don’t seem to make any sense autobiographically, with their fantasy of married bliss. Curious.

Darcy Moore

Thank you, Douglas. I also wonder how cognisant Cardigan and Orwell were of each other at Eton and afterwards. Surely Orwell would have read about his escape back to England after the disastrous fall of France? You will have to stay tuned for the next piece I write about Tunnard-Moore. There are some very interesting connections indeed.

Peter Marks

You present an fascinating set of connections clearly and authoritatively. It’s another great example of your research skills and your webcraft. The piece as much as anything reminds me of how interconnected the elites were/are in England, but also of how the gradations were/are able to be deployed to the benefit of the powerful. There are also the obvious gender disparities in terms of power, something Anna Funder is very strong on in Wifedom. Jacintha Buddicom appears to have been extremely treated poorly yet again. You wonder, at one point, if the ‘Colin’ of her poetry is Cardigan (you say that is her pseudonym for him) or if the poetry dedication refers to Thomas Turnard-Moore. I’m not quite sure why given the pseudonym there is any question. Possibly I’m missing something. Still, poetry needn’t be biography. Then there are the other women in Cardigan’s life–at least the public ones. To write off a suicide as part of a wife’s ‘Bad Family History’ seems an extremely callous if no doubt expedient and possibly much-used way of saving one’s family name. Cardigan sounds a complete bastard.

A few final points:

1) at the end you have a heading “More to Consider”. Is that something you intend to chase up, or are you using it as a prompt for others?

2) You mention an ‘inglorious ancestor’ of Cardigan’s who had gained immortality by leading the Charge of the Light Brigade. But ‘immortality’ hardly suggests anything inglorious. Indeed, Tennyson’s rousing poem condemns the someone who ‘had blundered’ while immortalising at length the ‘Noble six hundred’. Would Cardigan have seen the ancestor as inglorious?

3) Because you present the sequence of events in Cardigan’s life chronologically it might be better to place the following sentences after rather than before the headline ‘Suicide’: “This was to be a a (sic) truly horrible month and year for Cardigan. One imagines he was supported by one of his closest friends, Prosper, at this time of terrible sadness and (very public) turmoil.” It sits a little oddly in the sequence, otherwise. And you give the game away about the horrible month and year. The headline Suicide has more dramatic effect, I think. Probably it’s just me.

Please feel free to take or leave these suggestions as you choose.

All the best

Peter

Darcy Moore

Thank you, Peter. I have made some edits based on your feedback. Thank you. I do think the incompetent ancestor was inglorious but agree that he would not have been viewed that way by his family. The timeline for the affair is unclear and there are some logical inconsistencies with Buddicom’s poetry – but, of course, this is quite speculative (even from the family members).

Douglas Kerr

Splendid. You seem to have hit the bull’s eye with Cardigan. Is there any indication that he and Orwell met, after Eton? With the Buddicom and Quennell connections it seems possible. They do however seem almost complete opposites. Poor Jacintha. If she was C’s mistress for 30 years that must have coincided with at least two and probably all of his marriages.

You say categorically that Cardigan was the man. Perhaps in due course you will be able to say why you are certain of this.

On the other hand, if Cardigan was Colin in the Compleate Workes, the Tapestry poem makes no sense autobiographically (and how else can it be read?).

By the way the reporting of the suicide of Lady C is rather shocking. There is a clear implication that her mother’s suicide indicates a genetic inclination to unstable and self-destructive behaviour in the female line. ‘Bad family history.’ It’s the coroner himself who brings this up. I don’t think this could happen today. Cardigan himself is protected by both coroner and press, as you would expect.

Guy Loftus

Thanks Darcy for sharing this with such clarity and purpose (you have illuminated a trail for us to follow, a key in Jacinta’s poetic code to see where it will take us). I agree – there is much more to uncover and this is an excellent place to start. I think one of the things that compels us about Orwell is how he was able to occupy both planes (parallel and perpendicular) simultaneously. The person, in a way, who can help us to understand how may be Prosper. All the correspondence I have seen between Eric and Prosper have been about hunting, shooting and fishing – there seems to be no other depth to their relationship apart from the need to provide a legitimate portal to Eric’s relationship with Jacintha (what sibling hasn’t seen how you can disguise your real purpose by being a friend to all the family). Eric had to sustain the outward appearance of his class on one plane to reach Jacintha on their cerebral “other” plane (where George Orwell was to emerge). He used that connection (Prosper) to get back to Jacintha when he returned from Burma but it was too late. Perhaps Cardigan also found Prosper a convenient or even a necessary portal to Jacintha.

Forgive me indulging in planes (I blame you for inspiring it) but Jacintha was pantheist after all. I did wince at the bitter irony that both Jacintha and Eric on their shared plane yearned to study at Oxford; both were denied that possibility by over-bearing parents. Those who did go to Oxford (Prosper and Cardigan) were too incapacitated by entitlement on their single plane to benefit from doing so. That is the real tragedy for me.

Eric, Cini & Tom – Darcy Moore

[…] the father of Buddicom’s child has always been shrouded in secrecy, as was that of the “peer of the Realm” with whom she refused to marry but sustained an affair for more than three decades. The […]

Orwell: the Map & the Territory – Darcy Moore

[…] unpublished book of poetry (publicised in an essay by Eileen Hunt in 2021). 1974 – The “peer of the Realm” with whome Jacintha conducted an affair for thirty years dies – Eric & Us: A […]