“When Eric returned to England in 1927, he spent a fortnight with Auntie Lilian at Ticklerton, where Prosper and Guiny were then staying. But completely unavoidable circumstances prevented me from joining the party.” Jacintha Buddicom, Eric & Us (1974)

“… a year before Eric arrived back from Burma, she thought she had finally fallen in love. The tragic result of such a mistake would ruin her life. Eric, on his return in 1927, lost no time in contacting the Buddicoms and was invited to join Prosper and Guiny at Ticklerton. There was no Jacintha – and the family were evasive and embarrassed on the subject so that Eric must have assumed that, even after all this time, she was still angry with him and would never forgive his momentary fall from grace. The tragedy is that in fact, Jacintha had just, in May 1927 (sic), given birth to her daughter Michal Madeleine… The father escaped abroad as soon as her condition was discovered and so the baby was adopted…” Dione Venables, Eric & Us (2006)

Eric Blair arrived at Ticklerton Court in Shropshire on the 23rd August 1927 with the intention of proposing marriage to Jacintha Buddicom. On arrival, he was met by his mother, Ida Blair, who had been residing here with Aunt Lilian for the previous month. As we now know, Jacintha (“Cini” to friends and family) had been unavoidably detained due to the birth of her child rather than a wish not to see Eric.

The identity of the father of Buddicom’s child has always been shrouded in secrecy, as was that of the “peer of the Realm” with whom she refused to marry but sustained an affair for more than three decades. The secrets, gaps and silences are understandable. However, uncovering these events from nearly a century ago has the potential to reveal more about Eric Blair’s motivations to become a certain kind of writer – one bitterly obsessed with social class and ambitious for artistic, as well as commercial success – than his biographers have previously understood.

The Birth Certificate

“There was an Aunt Ivy Limouzin and an Aunt Nellie, as I remember. One or two of these aunts and their friends were Militant Suffragettes. Mrs Blair was in sympathy, but not so active. Some of this contingent, Eric said, went to prison and on hunger-strike as well as more moderately chaining themselves to railings.” Jacintha Buddicom

Jacintha’s child’s birth certificate is a rich source of information. “Michal Magdalen Tunnard-Moore” was born at “1 Ladbroke Square” on the 22nd July 1927 (not in May) and Jesse Emily Rhind listed as being “present at the birth”.

This address in North Kensington was the site of the Baby Clinic and Hospital originally established by the Women’s Labour League due to the high infant mortality rate in the neighbourhood. Founded as a memorial to Margaret MacDonald (she was the chair of the League and the wife of the Labour Party leader, Ramsay MacDonald) and Mary Middleton (the League’s secretary and wife of James Middleton, the General Secretary of the Labour Party).

At the time Jacintha gave birth, Ishbel MacDonald (1903-1982) was closely connected to both Ramsay MacDonald’s political career and the causes championed by her mother. During this period she was an “Independent Socialist” and had been elected to the London County Council. Her brother, Malcolm MacDonald, was a brilliant debater who knew some of Orwell’s Eton peers. Ishbel’s correspondence reveals that the Baby Clinic, which she continued to support, was an important aspect of her mother’s legacy.

Orwell’s aunt, the suffragette, Esperantist, literary scholar and actress Nellie Limouzin had lived nearby the clinic, at 195 Ladbroke Drive, for at least two decades (leasing that apartment until April 1928). Aunt Nellie, an inveterate writer of letters to editors, which reveal the breadth of her activism, was a feminist with extensive connections to important figures in the suffragette movement, including the Pankhursts.

Limouzin was associated with many organisations that successfully built political pressure for change. One of these was the Women’s Freedom League, which had the motto ‘Unity in Adversity’ and was affiliated with the Women’s Labour League (who founded the Baby Clinic). Members attended joint conferences and:

“A special suffrage edition of the League Leaflet was issued late in 1912 (no. 23), a statement of the Labour Party position on suffrage and that the League was working for its achievement.” (Collete: 146)

Mrs Rhind, who is noted on the birth certificate and delivered Jacintha’s baby, was (like Ida Blair) a registered midwife and a significant benefactress of the Clinic. She owned the property and lived on site with a Major Buist. Rhind had lived in this neighbourhood, at various addresses, for almost as long as Aunt Nellie. During 1929, she paid for the clinic to be equipped with an up-to-date operating theatre, paid for furnishings and fittings, a Frigidaire and wireless installation. There was central heating and the site could accommodate 32 cots.

On the 1927 electoral register, Rhind is listed with the bolded initials SJ indicating she was a “Special Juror”. The main difference between a “special jury” and a “common jury” was a matter of wealth related to the rateable value of the house. Mrs Rhind was another wealthier woman with a social conscience.

Jacintha had chosen to give Michal the father’s surname on the birth certificate. Who was Tunnard-Moore?

Thomas Tunnard-Moore (1904-1984)

“And then there was Prosper at Oxford, with his – as usual – numerous Oxford friends, some of whom became my friends as well.” Jacintha Buddicom

The Buddicom family had been connected to Brasenose College, University of Oxford since a great-grandfather, Robert Joseph Buddicom had attended in 1833. Jacintha met Thomas Charles Poynder Tunnard-Moore (and another lover, the Earl of Cardigan) via her brother, Prosper Buddicom (1904-1968).

Jacintha reputedly had many “admirers” and was “adept at keeping a stream of enthusiastic suitors at arms length” until she fell in love with Tunnard-Moore who had a privileged background. His family resided at Frampton Hall, in Lincolnshire.

Tunnard-Moore’s maternal line were Anglo-Indians. His mother and grandmother had both been born in India where his grandfather, Reverend Leopold Poynder (1818-1904) served as a chaplain (1847-66). Poynder’s diary and memoirs record his experiences during the 1857 Indian Mutiny in Bareilly (Orwell’s father served here as an Opium Agent in the latter part of the 19th century).

Tunnard-Moore, like his Poynder ancestors, attended Charterhouse from 1918-1921 and was in Gownboys House. He appears to have had a non-eventful time at the school and does not seem to have held any positions in sporting teams or societies.

Tunnard-Moore applied to Magdalen College at the University of Oxford on the 25 April 1922. He had not yet sat responsions (exams taken prior to matriculation) but hoped to read for a History degree. Students could submit an essay in support of their application, or alternatively, they could offer a ‘special subject’. Tunnard-Moore offered Chemistry. The books he studied in preparation for his application included Virgil’s Aeneid (Books I & II) and, ironically considering he would desert his pregnant girlfriend, Molière’s, Tartuffe.

In his first year at Magdalen, Tunnard-Moore read for Prelims in Agriculture. His tutor was Malcolm Henry MacKeith (1895-1942) and he roomed with Godfrey Sturdy Incledon Webber (1904-1986) an aristocrat who became the Sheriff of London in 1968 after rising to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel during the war. In his second and third years, Tunnard-Moore read French for the Pass degree course. In his final term he was tutored by Anthony William Chute.

Tunnard-Moore played hockey for his college and is sitting at the front on the right in this photo the 1924-25 season.

The relationship had blossomed by 1926 into something that Buddicom considered serious. Her “love” was not practically reciprocated and Tunnard-Moore fled the country on learning she was pregnant, possibly due to parental pressure. There have been suggestions he absconded with a male lover to the continent.

Tunnard-Moore’s obituary reveals he was a student and lecturer at “various continental universities” between 1927-30. He was awarded a Master of Arts from the University of Montpellier in 1930. He is listed, in the Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, as having gained a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Oxford on the 21 December 1928 suggesting he was not abroad for three years.

During the next decade, Tunnard-Moore was a schoolmaster, farmer and businessman before commencing a position at the outbreak of World War II with the British Council.

Like the Earl of Cardigan, Tunnard-Moore was wealthy enough to afford a passion for expensive automobiles. He was in partnership with ex-Etonian, Robert Arbuthnot (1914-1946) a gay racing-car driver from a banking family, who owned a car restoration business, High Street Motors in London and Watford.

In 1941, Tunnard-Moore purchased a 1936 Bugatti Type 57SC Atlantic from another rich son of a banker, Victor Rothschild. He sold it to Arbuthnot who parted with it in 1944, just two years before he was killed in a motor accident. It has been sold many times since and continues to win prizes at vintage car shows.

Tunnard-Moore and Arbuthnot were friends, at the very least, and enjoyed a privileged life with opportunities for excess. This came with consequences. Jacintha suffered due to her relationship with Tunnard-Moore but Miss Violet Robson (interestingly, also known as Vera Holtman) fared much worse.

The British Council

Tunnard-Moore worked for the British Council between 1939-1948. He was in charge of the Council’s Educational Appointments department from 1940 and was appointed Director, Dominions and India in the Empire Division in 1945.

Sir James Angus Gillan (1885-1981), who headed the Commonwealth and Empire Division of the British Council (1941-1949), was an alumnus of Magdalen College and employed Tunnard-Moore as his assistant. In late 1946, while working in this capacity, Tunnard-Moore negotiated important meetings with the “wary rather than enthusiastic” Jawaharlal Nehru, who became India’s first Prime Minister in 1947. Ultimately, with Nehru’s blessing, the British Council was able to establish a significant role in an independent India.

Did Orwell come in contact with Tunnard-Moore during the war? We do not know but considering Orwell worked as BBC Talks Assistant/Producer, writing and programming propaganda for broadcast into India during 1941-1943, they shared overlapping professional and literary circles.

Eric Walter Frederick Tomlin (1913-1988) was friends with T.S. Eliot and while he was “doing some propaganda work for the BBC” learned of “a newly-formed organisation called the British Council” whose “aim was to counter Axis influences and propaganda”. He quotes from a letter Eliot (who was employed by the British Council) wrote to him on the 8 April 1940:

Dear Tomlin,

Some remarks I made, without mentioning your name, in writing to the British Council, have elicited a reply from someone there named T. P. Tunnard-Moore, whom I have never met, and whose name is not on the letterhead, so I don’t quite know what his position is. But the point is that he says the British Council has now received permission to send out men down to 25, and, he adds, ‘even to extract them from the army if their qualifications are sufficiently outstanding. So send your man along, or let him write, but don’t let him construe this as a promise .

If you want to write to him, mention that this came through correspondence with me, and also that I should be glad to be one of the people to speak for you if necessary.

Yours ever,

T.S. Eliot.

William Empson (1906-1984) also knew Tunnard-Moore and Orwell. “Bill” Empson (and his wife Hetta) had met Orwell on a course for new employees famously known as the “Liars School of the BBC”. They became firm friends, working alongside each other for the next two years.

Empson hosted parties attended by many literary figures, BBC and British Council employees. He also corresponded with Tunnard-Moore in an attempt to gain a position with the British Council in early September, 1945. Although purely (but deliciously) coincidental, Empson had written to Orwell just 10 days before about perceptions of “Tory propaganda” in Animal Farm.

Further Biographical details

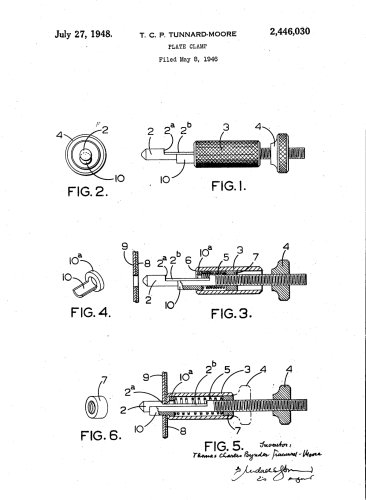

After resigning from the British Council in 1948, Tunnard-Moore became the Managing Director of Moore & Tucker, Ltd.. During this year he successfully patented a plate clamp.

In late October 1949, the 45- year-old Tunnard-Moore married a woman over twenty years younger, Valerie Mary Tucker (1926-2005), at Christchurch priory. A son, Thomas Tunnard-Moore (1951-1969), was born in 1951.

Tunnard-Moore was a member of The Savile Club (as were HG Wells and Compton Mackenzie whom Orwell knew) and the M.C.C.. He resided at 118 Cromwell Road, SW7 until moving to Guernsey. His only son died, aged 18, in a car accident returning home from a Christmas party.

Tragically Michal, the daughter he had abandoned in 1927, was also killed in a car accident in 1995.

After a “long illness borne with courage and laughter” Tunnard-Moore died in the final month of 1984. Jacintha lived for another decade, dying in 1993, aged 92. She never married and had no other children.

Conclusion and a Little Speculation

The story of Eric Blair’s connection to the Buddicom family is important to understanding the genesis of his evolution into the “FAMOUS AUTHOR” he dreamt of becoming in childhood conversations with Jacintha.

Recovering the barely discernible timeline of life events, from when he departed Burma in 1927 until arriving in Paris almost a year later, is far more important to understanding his motivations for becoming a writer very conscious of social class than previously envisaged by biographers. The life drama that Eric Blair experienced during this summer in 1927, culminating in his announcement while holidaying in Cornwall with his family that he intended to become a writer, is particularly in need of further analysis.

One significant example, although speculative, is that Jacintha knew of the Baby Clinic and Hospital through information provided by Orwell’s mother or aunt. There is strong circumstantial evidence this may have been the case. If correct, it seems likely Orwell knew Jacintha had a child which may have led him to believe she might marry him and move to Burma where nobody would know the child was illegitimate. The fact that Ida was at Ticklerton Court three days after Michal was born and Eric Blair had been with Nellie in Paris by early August 1927 are important pieces of the jigsaw.

If this is indeed can be proven, how does it change the representation of Orwell that has emerged, since the 2006 publication of the postscript version of Eric & Us, in regards to his vexed relationship with Jacintha Buddicom? What does the new information about the Earl of Cardigan and Tunnard-Moore tell us about Orwell’s attitude to class?

More anon.

REFERENCES

Bowker, Gordon, The Trail That Never Ends: Reflections of a Biografiend, Finlay Publisher, 2010

Buddicom, Jacintha, Eric & Us: A Remembrance of George Orwell, Frewin, 1974

Buddicom, Jacintha & Venables, Dione (2006) Eric and Us: The Postscript Edition, Finlay

Buddicom, Lilian (1927) Diary (unpublished)

Byrne, Alice, The British Council in India, 1945-1955: Preserving “old relationships under new forms”, Laurent DORNEL et Michael PARSONS, Fins d’empires / Ends of Empires , 5, Presses de l’Université de Pau et des pays de l’Adour, pp.119-135, 2016, Figures et perspectives ; Espaces, Frontières, Métissages, 2-35311-077-0. ffhal-01420450

Charterhouse Archives

City of London Archives

Collette, Christine, For Labour and for Women: The Women’s Labour League 1906–18, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1989

Crick, Bernard, George Orwell: A Life, London: Penguin, 1992

Crook, J. Mordaunt, Brasenose: The Biography of an Oxford College, Oxford University Press, 2009. 574pp.

Eastment, Diana Jane, The Policies and Position of the British Council from the Outbreak of War to 1950, University of Leeds, School of History, Thesis (Doctor-of Philosophy), 1982

Empson, William, Selected letters of William Empson, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008 pp. 147-149

Empson, Jacob, Hetta and William: A Memoir of a Bohemian Marriage, London: Author House, 2012

Evening Chronicle, 24 December, 1969

Gross, Miriam (ed.), The World of George Orwell, Weidenfield and Nicholson, 1971

Haffenden, John, William Empson: Volume I – Among the Mandarins, Oxford University Press, 2005

Haffenden, John, William Empson: Volume II – Against the Christians, Oxford University Press, 2006

Magdalen College Archives

Middlesex Independent and W. London Star, 14 October 1949

Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette, 21 December 1928

Rudd, Jill and Gough, Val (eds), Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Optimist Reformer, University of Iowa Press, 1999

Simony, Lauriane, Le premier British Council en Birmanie entre 1948 et 1955: politique linguistique et diplomatie culturelle au lendemain de l’indépendance, Sciences de l’Homme et Société, 2015. ffdumas-02184601f

Swanage Times & Directory, 17 March 1923

Times, 15 December, 1984

Tomlin, E.W.F, T.S. Eliot: A Friendship, London: Routledge, 1988, p130

Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 24 November 1930

Acknowledgements

Archivists who are willing to genuinely assist with research challenges make a huge difference, especially when those documents have not been digitised. Warm thanks are due to Rebecca Grafton, Stephen Witkowski and Emily Jennings.

I am extremely grateful to Melanie Scott for sharing what she knows about her grandmother, Jacintha Buddicom, Her generosity and kindness in granting permission to use the photographs and documents in her possession is very greatly appreciated. Information provided over several years by Dione Venables and conversations with Liam Hunt have also proven invaluable.

Unkle Cyril

Congratulations on a great piece of research, and a very interesting read, that prompts musings on the lives of the people of the times, and relationships.

Orwell & the Earl of Cardigan – Darcy Moore

[…] More anon. […]

Douglas Kerr

I quite agree with you in seeing the period from his return from Burma in 1927, to his return from residence in Paris, as both crucial and hitherto not well understood. So this research is useful and important. Keep it coming.

You make the intriguing speculation that, especially if GO’s mother or aunt knew of the Baby Clinic and recommended it to poor Jacintha, then Orwell may well have known about Jacintha’s child, and wanted to marry and take her back to Burma, where the illegitimacy of the child would be unknown. This is fascinating – appropriately, it sounds like a Somerset Maugham story. If you are right, then J must have turned him down, or at least somehow made sure the proposal was never made. Alternatively, if Ida and Nellie did know about the pregnancy, but kept it from Orwell, what a sad situation for all parties! Orwell must have supposed that J was avoiding him because she had not forgiven him for his earlier advances.

One thing that makes me hesitate to accept the speculation that Orwell knew, is the letter, actually letters, he wrote to Jacintha after she made contact him much later, in February 1949 (CWGO XX:42-44). There is nothing conclusive here, and O sounds friendly if a bit cautious, writing to an ex-girlfriend he hasn’t seen for nearly 30 years. But there doesn’t seem to be any recognition of Jacintha’s history. (‘Are you fond of children?’ he asks her.) Would he have written letters like this if he was aware of her tragedy (if that’s what it was)? Or might he be not sure she knows he knows?….. And so on.

(And a propos the appearance of motor cars in Moore’s story, as in Cardigan’s… this is another instance of the importance of motoring (and motor sport and motor accidents) for men of Orwell’s class and above! I think of the adventures of Agatha Runcible in Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies for example. But the only motor car I can think of in Orwell’s work is in Coming Up for Air. Perhaps there are others? But it makes me think: could Orwell drive?)

Darcy Moore

Thanks Douglas. I have thought a great deal about the “are you fond of children?” line in his letter to Jacintha. It can be read more than one way and, considering the lies and dissembling, is not a conclusive answer to the question did he know of the baby? I speculate that he did for several reasons including the fact that he arrives in England and goes straight to Ticklerton to propose, knowing his mother was present (and had been for 4 weeks). This is very different from the two usual versions of the story where she is not present. The North Kensington clinic is also new knowledge.

Yes, Orwell did indeed have a licence which you can see at the Orwell Archive. Here is his 1934-1935 one: https://ucl.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/delivery/44UCL_INST:UCL_VU2/12358715570004761

John Rodden

Darcy, I gather that you are saying, in your reply to Douglas, that Orwell knew as a result of letters from his mother? Or is there someone more likely? Did a falling out between the mothers occur b/c of the visit? Or one or more phone calls that occurred between E and J at this time? When you speak of “lies and dissembling,” are you suggesting specifically that Orwell’s question about children is coded in such a way as to invite her to open up about the child? Or to open up about asking him if he knew about it? Yes, it can certainly be read in “more than one way”…. as your exchange with Douglas reflects…. so I wonder what are you are specifically suggesting here about how to read it…. or at least the most plausible “ways” to do so.

Just a reflection of how stimulating and valuable this research is…. Another tour de force.

Darcy Moore

Hi John, I speculated about the possibility Orwell knew of Jacintha’s pregnancy based on chronology, his movements & geography. More evidence is required but it is clear secrets abounded – some of which are yet to be discovered.

Orwell: the Map & the Territory – Darcy Moore

[…] Jacintha (which unsurprisingly ended their friendship); that Jacintha had a child in 1927 (to an un-named father); and, that she was in a long term affair with a “peer of the Realm” 2010 – a […]

Orwell’s Family: Aunt Nellie – Darcy Moore

[…] network of Nellie’s connections – political, theatrical and literary – are becoming more visible. She had friends and associates who can be identified as belonging to the British Esperanto […]