‘The rat,’ said O’Brien, still addressing his invisible audience, ‘although a rodent is carnivorous. You are aware of that. You will have heard of the things that happen in the poor quarters of this town. In some streets a woman dare not leave her baby alone in the house, even for five minutes. The rats are certain to attack it. Within quite a small time they will strip it to the bones. They also attack sick or dying people. They show astonishing intelligence in knowing when a human being is helpless.’

George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four

Why is George Orwell’s work so infested with rats? His books, correspondence, diaries and essays detail this obsession – which intensified as he aged. However, new evidence has come to light that the foundations of his fear and loathing may have commenced in infancy, in a cot in Motihari, India.

The apotheosis of his revulsion is evident in his last novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four. Few readers ever forget Room 101, deep inside the ironically named Ministry of Love, where political prisoners endure ‘the worst thing in the world’. For Orwell’s protagonist, Winston, this happened to be rats:

There was an outburst of squeals from the cage. It seemed to reach Winston from far away. The rats were fighting; they were trying to get at each other through the partition. He heard also a deep groan of despair. That, too, seemed to come from outside himself.

O’Brien picked up the cage, and, as he did so, pressed something in it. There was a sharp click. Winston made a frantic effort to tear himself loose from the chair. It was hopeless; every part of him, even his head, was held immovably. O’Brien moved the cage nearer. It was less than a metre from Winston’s face.

‘I have pressed the first lever,’ said O’Brien. ‘You understand the construction of this cage. The mask will fit over your head, leaving no exit. When I press this other lever, the door of the cage will slide up. These starving brutes will shoot out of it like bullets. Have you ever seen a rat leap through the air? They will leap onto your face and bore straight into it. Sometimes they attack the eyes first. Sometimes they burrow through the cheeks and devour the tongue.’

The cage was nearer; it was closing in. Winston heard a succession of shrill cries which appeared to be occurring in the air above his head. But he fought furiously against his panic. To think, to think, even with a split second left – to think was the only hope.

Suddenly the foul musty odour of the brutes struck his nostrils. There was a violent convulsion of nausea inside him, and he almost lost consciousness. Everything had gone black. For an instant he was insane, a screaming animal. Yet he came out of the blackness clutching an idea. There was one and only one way to save himself. He must interpose another human being, the body of another human being, between himself and the rats.

The circle of the mask was large enough now to shut out the vision of anything else. The wire door was a couple of hand-spans from his face. The rats knew what was coming now. One of them was leaping up and down, the other, an old scaly grandfather of the sewers, stood up, with his pink hands against the bars, and fiercely sniffed the air. Winston could see the whiskers and the yellow teeth. Again the black panic took hold of him. He was blind, helpless, mindless.

‘It was a common punishment in Imperial China,’ said O’Brien as didactically as ever.

Even prior to publication in 1949, Orwell’s vivid prose deeply affected those involved in the production of the novel. Orwell’s typist, Miranda Wood, found it hard to get “the rat torture scene” out of her mind even after the manuscript of Nineteen Eighty-Four was dispatched to the publisher, Secker & Warburg.

Fredric Warburg wrote a report on that manuscript noting that it was one of the “most terrifying books” he had ever read and that Orwell had given “full rein to his sadism and its attendant masochism, rising (or falling) to the limits of expression in the scene where Winston, threatened by hungry rats which will eat into his face…”.

Many viewers of the controversial BBC television adaptation of the novel in 1954 had the same horrified reaction as Wood and Warburg. Michael Radford, in his extremely successful film adaptation, conveyed the horror of Winston’s torture to a new generation. The viewer experiences the sheer visceral terror of those ‘old scaly’ rats with their ‘yellow teeth’ poised to attack Winston’s eyes or burrow through his cheeks to ‘devour the tongue’ as O’Brien torments the prisoner with his commentary.

Orwell’s fascination with rats, evident for many years before the publication of this final novel, chart both his personal and literary experiences.

Orwell’s rat obsession

The taxi driver said something in a reassuring tone, & after somebody had looked out of an upper window, the door opened & an enormously fat man came out, carrying a lantern in his hand. The lantern showed a bedraggled dead rat lying on the doorstep, & shone dimly upon the man’s huge belly, for he was half naked, & his great pockmarked face…

from a very early draft of Burmese Days (1934)

D.J. Taylor has explored Orwell’s ‘rat obsession’ more thoroughly than other biographers noting, in On Nineteen Eighty-Four: A Biography, that it is such a fixture of his printed work “that he can often seem like a kind of literary pied piper dancing at the head of an unappeasable furry brood that winds on from one book to the next”.

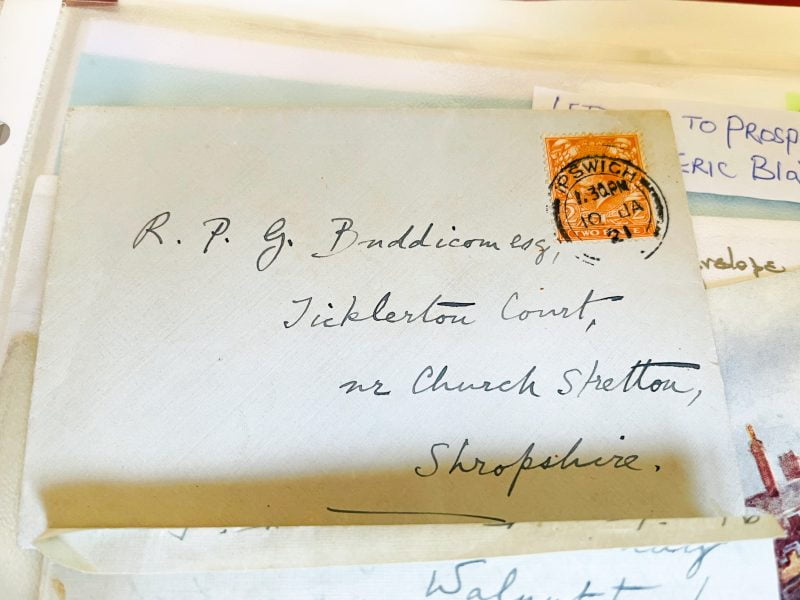

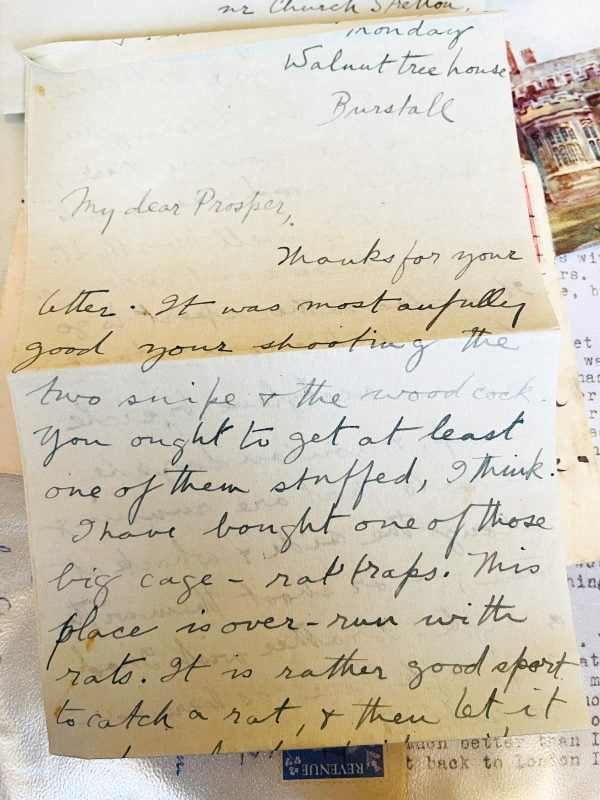

It is worth looking into the nooks and crannies of Orwell’s less well-known writing to explore this interest in rats further. In a letter written* to his friend Prosper Buddicom, in 1921 while a teenager, Orwell explained his approach to killing rats:

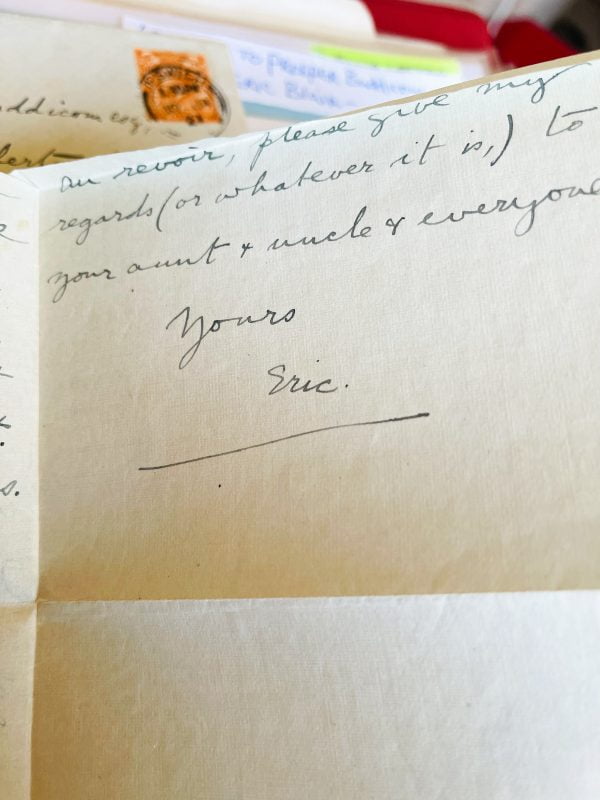

My dear Prosper,

Thanks for your letter. It was most awfully good your shooting the two snipe & the woodcock. You ought to get at least one of them stuffed, I think.

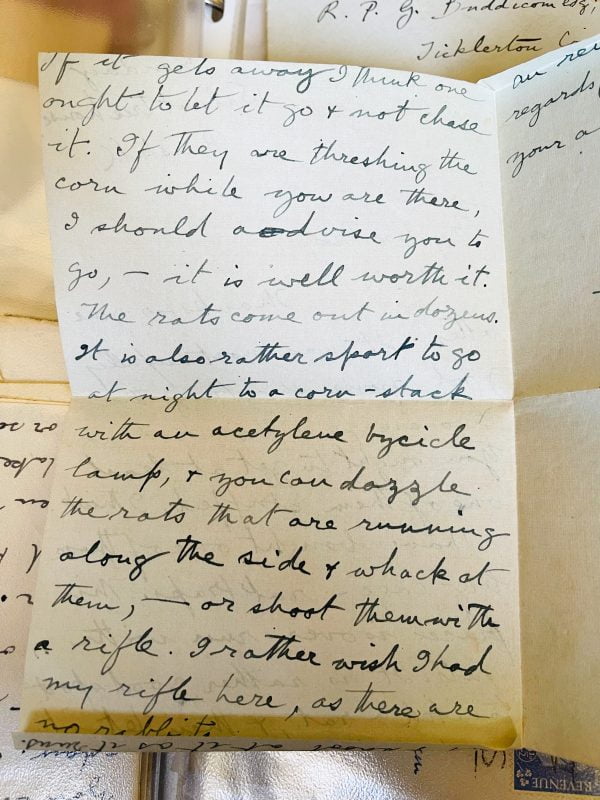

I have bought one of those big cage-rat traps. This place is over-run with rats. It is rather good sport to catch a rat, & then let it out & shoot at it as it runs. If it gets away I think one ought to let it go & not chase it. If they are threshing the corn while you are there, I should advise you to go,—it is well worth it. The rats come out in dozens. It is also rather sport to go at night to a corn-stack with an acetylene bycicle (sic) lamp, & you can dazzle the rats that are running along the side & whack at them,—or shoot them with a rifle. I rather wish I had my rifle here, as there are no rabbits.

Au revoir, please give my regards (or whatever it is,) to your aunt & uncle & everyone.

Yours

Eric.

Orwell’s diaries are filled with pithy comments regarding rats that most people would not bother to record. Catching a rat in a trap is usually worth diarising it seems. He has limited success poisoning rodents and finds an “almost fossilised” one in the rubbish. Rats are possibly the culprits eating the eggs from his chicken coop. Always a close observer of nature, Orwell expresses surprise “they bred so late in the year” is impressed that “a barn owl destroys between 1,000 and 2,000 rats and mice in a year”.

In one entry, written just prior to the outbreak of WWII, Orwell notes the “rat population of G. Britain estimated at 4–5 million”. We can see his research data being employed in Nineteen Eighty-Four:

‘Rats!’ murmured Winston. ‘In this room’.

‘They’re all over the place,’ said Julia indifferently as she lay down again. ‘We’ve even got them in the kitchen at the hostel. Some parts of London are swarming with them. Did you know they attack children? Yes, they do. In some streets a woman daren’t leave her baby alone for two minutes. It’s the great huge brown ones that do it. And the nasty thing is that the brutes always—’

‘Don’t go on!’ said Winston, with his eyes tightly shut.

While living at Barnhill, on the Isle of Jura where he wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell noted in his diary (12th June 1947):

Saw the buzzard carrying a rat or something about that size in its claws. The first time I have seen one of these birds with prey.

Five rats (2 young ones, 2 enormous) caught in the byre during about the last fortnight. These rats seem to let themselves be caught very easily. The traps are simply set in the runs, unbaited & almost unconcealed. Also no precautions taken about handling them. I hear that recently two children at Ardlussa were bitten by rats (in the face, as usual).

Orwell is particularly obsessed with babies being menaced by rats. Gulliver’s Travels, a book that he held in the highest esteem (“If I had to make a list of six books which were to be preserved when all others were destroyed, I would certainly put Gulliver’s Travels among them”) and read from his boyhood til the last years of his life (see Politics vs. Literature: An Examination of Gulliver’s Travels) has an episode that is particularly pertinent to his own childhood experience (discussed later in this post):

The bed was eight yards from the floor. Some natural necessities required me to get down; I durst not presume to call; and if I had, it would have been in vain, with such a voice as mine, at so great a distance from the room where I lay to the kitchen where the family kept. While I was under these circumstances, two rats crept up the curtains, and ran smelling backwards and forwards on the bed. One of them came up almost to my face, whereupon I rose in a fright, and drew out my hanger to defend myself. These horrible animals had the boldness to attack me on both sides, and one of them held his fore-feet at my collar; but I had the good fortune to rip up his belly before he could do me any mischief. He fell down at my feet; and the other, seeing the fate of his comrade, made his escape, but not without one good wound on the back, which I gave him as he fled, and made the blood run trickling from him. After this exploit, I walked gently to and fro on the bed, to recover my breath and loss of spirits. These creatures were of the size of a large mastiff, but infinitely more nimble and fierce; so that if I had taken off my belt before I went to sleep, I must have infallibly been torn to pieces and devoured. I measured the tail of the dead rat, and found it to be two yards long, wanting an inch; but it went against my stomach to drag the carcass off the bed, where it lay still bleeding; I observed it had yet some life, but with a strong slash across the neck, I thoroughly despatched it.

Soon after my mistress came into the room, who seeing me all bloody, ran and took me up in her hand. I pointed to the dead rat, smiling, and making other signs to show I was not hurt; whereat she was extremely rejoiced, calling the maid to take up the dead rat with a pair of tongs, and throw it out of the window. Then she set me on a table, where I showed her my hanger all bloody, and wiping it on the lappet of my coat, returned it to the scabbard

Orwell could not escape rats in comics any more than in life or his writing. In Boys’ Weeklies, his ground-breaking essay on popular culture, he describes the cover illustrations:

On one a cowboy is clinging by his toes to the wing of an aeroplane in mid-air and shooting down another aeroplane with his revolver. On another a Chinese is swimming for his life down a sewer with a swarm of ravenous-looking rats swimming after him. On another an engineer is lighting a stick of dynamite while a steel robot feels for him with its claws. On another a man in airman’s costume is fighting barehanded against a rat somewhat larger than a donkey.

Orwell is rarely anything less than a contradictory, paradoxical figure. In 1948, he replied from his hospital bed in Hairmyres Hospital to a letter from Celia Kirwan with the most remarkable, surprisingly counter-intuitive, rodent anecdote from his time in Paris during the 1920s one could conceivably imagine:

How I wish I were with you in Paris, now that spring is there. Do you ever go to the Jardin des Plantes? I used to love it, though there was really nothing of interest except the rats, which at one time overran it & were so tame that they would almost eat out of your hand. In the end they got to be such a nuisance that they introduced cats & more or less wiped them out.

Sadly, Orwell was allergic to an experimental tuberculosis drug that would have saved his life. Around the same time he wrote to Kirwan, Orwell explained to another friend, employing another striking image, his plight:

I am a lot better, but I had a bad fortnight with the secondary effects of the streptomycin. I suppose with all these drugs it’s rather a case of sinking the ship to get rid of the rats.

He must have liked the turn of phrase, as he was still using it following year in correspondence:

If necessary I can have another go of streptomycin, which certainly seemed to improve me last time, but the secondary effects are so unpleasant that it’s a bit like sinking the ship to drown the rats.

Why rats?

Why was Orwell so obsessed with rats? What was the root cause (if any) of his revulsion and why did rodents occupy his thoughts and fuel his creative energy so vividly?

Orwell’s parents met in India and married during 1897. Their only son was born in 1903 in Motihari, where Richard Blair, his father, was stationed. However, Orwell was not to stay long on the sub-continent.

It was completely routine for the children of the officials working in the Indian Civil Service to return to be schooled in England while the men remained at their posts. Ida Blair, his mother, fled India with her two children sometime in 1904. A pressing public health issue and disturbing event in her home had hastened this departure.

The district was being ravaged by plague (Bowker). Since 1896, India had experienced two decades of high death rates from this disease but low monsoonal rains and the cooler temperatures in the north of Bihar, where Orwell’s family were stationed, made the rapid spread inevitable (Klein/Rogers).

The family had been living in one of the three colonial bungalows, at the European edge of the town, known as ‘Miscourt’ (an amalgam of ‘mess’ and ‘court’) overlooking the fields (Harding) when an incident that would horrify any parent occurred.

Orwell, sleeping in his cot, was bitten on the leg by a rat (Venables). Understandably, this horrifying incident hastened his mother’s departure with her children to England.

Prosper Buddicom enjoyed teasing Eric Blair about his fear of rats. Family diaries do reveal youthful conflict and rivalry between Prosper and Eric (Buddicom 1917). Eventually, in way of explanation, Eric revealed a tiny scar was on his leg.

Prosper’s sister, Jacintha Buddicom, was cynical that a rat had caused the injury when told this by the young Orwell and felt he was exaggerating. Her younger sister, Guinever, believed him (Venables).

This oral anecdote (discussed by both Guinever and Jacintha Buddicom multiple times with their cousin) about the infant Orwell being bitten by a rat does make a great deal of sense considering Orwell’s life long obsession with killing rats and concerns about the vulnerability of babies.

Generations of readers have asked the questions, did Orwell really shoot an elephant or witness a hanging in Burma? There has been considerable effort expended attempting to find autobiographical evidence that these two events happened but neither has been definitively proven. It is generally accepted that the answer to both questions is – probably!

Did Orwell tell his childhood friends the truth about being bitten by a rat?

Probably!

Featured image: ‘The Rat Cage’

REFERENCES

Bowker, Gordon (2004 [2003]) George Orwell, London: Abacus

Buddicom, Jacintha & Venables, Dione (2006) Eric and Us: The Postscript Edition, Finlay

Buddicom, Lilian (1917) Diary (unpublished)

Crick, Bernard (1992 [1980]) George Orwell: A Life, Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, second edition

Davison, Peter (2013) George Orwell: A Life in Letters, Liveright

Harding, L. (2000) Shadows of Orwell’, The Guardian, Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2000/jun/24/georgeorwell.classics [Accessed 23 July 2022].

Klein, I. (1988) ‘Plague, Policy and Popular Unrest in British India’, Modern Asian Studies, 22(4), 723–755. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/312523 [Accessed 23 July 2022].

Orwell, George (1997 [1949]) Nineteen Eighty-Four, The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. 9, London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1998) A Kind of Compulsion (1903-1936), The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. 10, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1998) It Is What I Think: 1947–1948, The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. 19, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Orwell, George (1998) Our Job is to Make Life Worth Living (1949-1950), The Complete Works of George Orwell, Vol. 20, Davison, Peter (ed.) London: Secker & Warburg

Rogers, L. (1928) ‘The Yearly Variations in Plague in India in Relation to Climate: Forecasting Epidemics’, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character, 103(721), 42–72. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/81315 [Accessed 23 July 2022].

Taylor, D. J. (2004) Orwell – The Life, London: Vintage

Taylor, D.J. (2019) On Nineteen Eighty-Four: A Biography, Harry N. Abrams. Kindle Edition.

Venables, Dione (2022) Interview, 9 July

*Special thanks to Dione Venables for her kindness and intellectual generosity.

A lengthier version of “Orwell’s Rats” is published in Vol. 7, No. 1 of George Orwell Studies

Orwell & Bedford – Darcy Moore

[…] in Mussoorie, just months before Eric was born. Young Eric spent less than a year in India before escaping the plague sweeping Bihar with his mother and sister to England. He would return to the subcontinent, in late […]