“I once too had known this Eric Blair. But I had never had cause to remember him. I had forgotten that he was called Eric Blair, I had forgotten the encounter, until, last week…”.

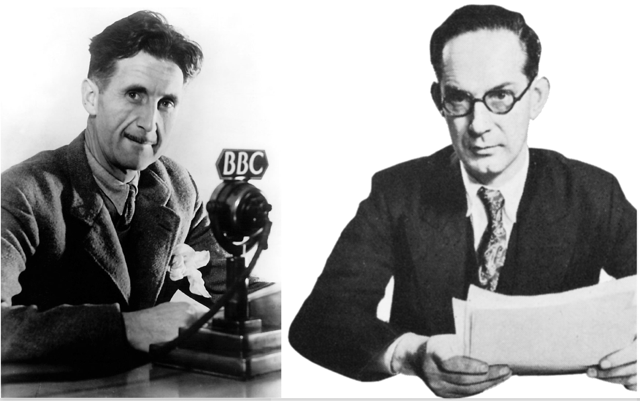

Geoffrey Grigson

Early next month I will give a talk for The Orwell Society in Polperro. Revisiting my research into Eric Blair’s experiences in Cornwall in preparation for the event resulted in a few more pieces of the jigsaw fitting into place. I previously speculated that Grigson may have known the young Eric Blair during their boyhoods. It is now possible to confirm that this was indeed the case.

Geoffrey Grigson (1905-1985) was a poet, magazine editor and naturalist born in Cornwall. He worked during WWII for the BBC, as did Orwell. Born just a few miles down the road from Polperro, he is an interesting source on the Perrycoste family, who greatly influenced both his and Orwell’s knowledge and love of nature. Grigson published many books about flora, including: Wild Flowers in Britain (1943); Flowers of the Meadow (1950); The Shell Guide to Flowers of the Countryside (1957); The Englishman’s Flora (1958). However, he is mostly known for founding New Verse (1933–9) where his own criticism of his contemporaries was “unsparing and at times ferocious”. He described the journal as a “malignant egg” and later regretted the “savage use of the billhook” so often on display in his reviews written for The Observer, The Manchester Guardian and The New Statesman.

Orwell’s friend and colleague, Julian Symons, described Grigson as:

“…tall, handsome, and enthusiastic, with an attractive blend of sophistication and innocence. The fierceness of his writing was belied by a gentle, sometimes elaborately polite manner. He distrusted all official bodies dealing with the arts, and served on no committees.”

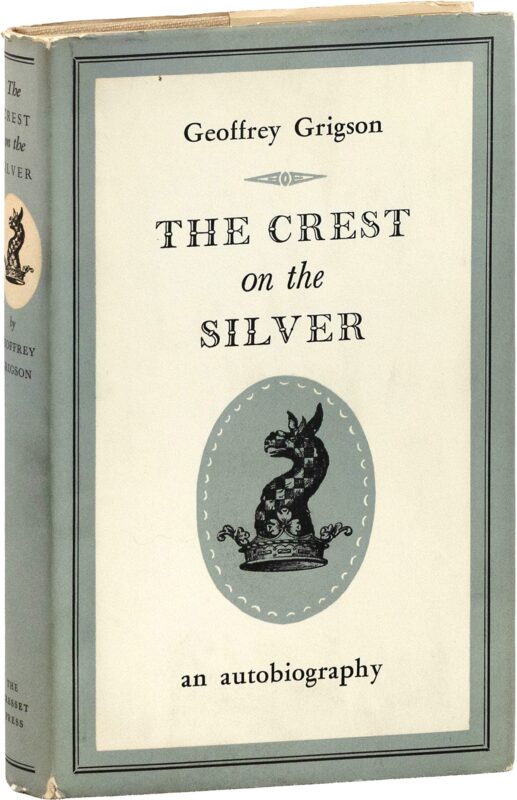

If you do not have time to read the original essay, here is what Grigson had to say about the Perrycoste family, referred to as the X-Ys, in The Crest On The Silver: An Autobiography (1950):

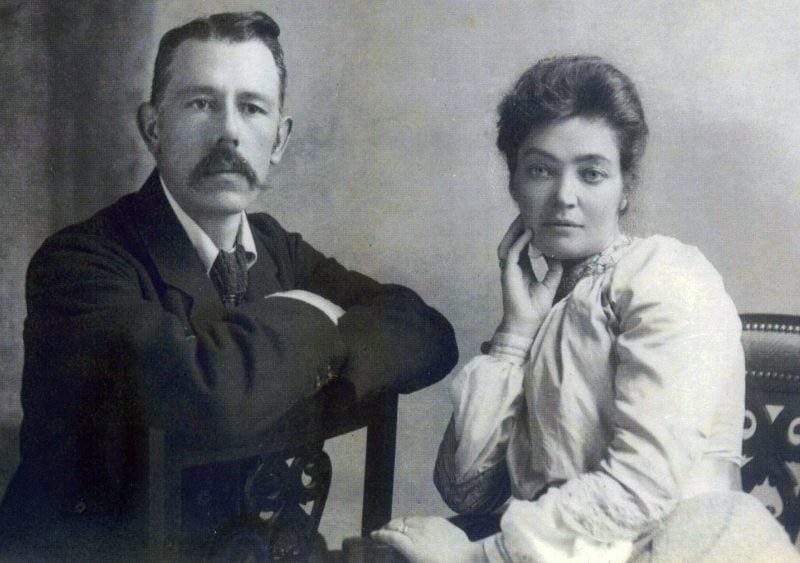

“A fairly close friend (“fairly close” is enough because the friendship dwindled during the years) was a woman of intelligence who lived in Polperro. She sketched, and gave oil-sketches of the rocks meeting the rocks to my mother who managed to conceal another bit of the drawing-room wall with them. She was also a botanist, in the commoner sense of one who knew her plants adventures in search of them, and contributed to the country flora. She was small and active, a fluffy red-cheeked little woman, not far from the untidiness into which she fell, who tricycled round the district, a thing, so far as I know, my mother never achieved. She married a strange man, who was a bogey. I must once have touched his velvet coat, which I always disliked. He was à scientist—perhaps a chemist—but either he or his wife came into money enough to build themselves a house, and live, and meditate at Polperro. He was also a rationalist, an atheist, and a Radical Wellsian figure, self-educated to some degree, and uncertainty in command of standard English pronunciation, a fault on which my mother would sharpen her claws.

There was an air of failure about this man, with his long face, his distant manner, his habit of disappearing in his house, his wispy moustache, which I felt. He always pronounced my name wrongly, “Well, Juffrey”, if I came to the house; and then disappeared. He was ungemütlich and a little pompous, and winter and summer he always bathed, nude or with a minimum of triangle, from a rock pool just round from the harbour. Genetics was one of his pursuits. He studied in-breeding in Polperro fishermen. His unreadable books were published privately, but he had friends in the more positive and less amateur world, among them Havelock Ellis; and I was surprised to find a few years ago that he had contributed an appendix to Havelock Ellis’s Studies in the Psychology of Sex. It was just as well no one knew that in Polperro, or in the vicarage. Polperro did not altogether appreciate him. At election time—he was friendly with the Foots, I believe, as well as being one of their supporters—Tory fishermen would take their trousers down on his doorstep and leave a token of their goodwill to be discovered there in the morning.

I wish now that we had known this family better than we did. There was an earnestness in the household, an activity outside the mere routine of staying alive, and a contact with professional artists and writers and men of science altogether lacking in the vicarage three miles away. But perhaps appearances interfered again. X-Y, hyphened, was not, well, not a gentleman, “and he was plain Y”, said my mother, “when his old father was alive.” My mother had a justifiable scorn for the creation of double-barrelled names as an easy way of assuming gentility and distinction. As children, we always heard criticism of the Polperro household, which the wife’s eccentricities did not diminish; we looked for oddity there and found it, and there was family hostility towards going to parties in the house. My mother was not interested in the husband, in the identification of plants, in tricycling, in bathing, in picnics, and eventually it became the habit in the family, though she was godmother to one of my brothers (in spite of her husband’s atheism) and though my father actually stood sponsor to her son, to speak of my mother’s old friend with contempt. Still that did not prevent kindnesses and encouragement from her, in one instance, for which I suddenly realise I must be grateful. She discovered my interest in plants, lent me floras, and helped me with identifications; and it was through her that I believed at one time I would make my living as a professional botanist or a forester.”

Grigson’s recollections are important as they provide an insight into the Perrycoste family who also influenced Orwell’s understanding of the natural world and more besides. One sentence – “there was an earnestness in the household, an activity outside the mere routine of staying alive, and a contact with professional artists and writers and men of science altogether lacking in the vicarage three miles away” – suggests Orwell too was exposed to wide-ranging intellectual endeavour and a creative milieu of individuals during his long summer holidays in Cornwall.

On Orwell

“When I was young and living in Cornwall near Polperro … I once too had known this Eric Blair. But I had never had cause to remember him … a skinny boy, I think on the beach at Lansallos, wearing one of those loose, shoulder-to-thigh bathing dresses which everyone wore.”

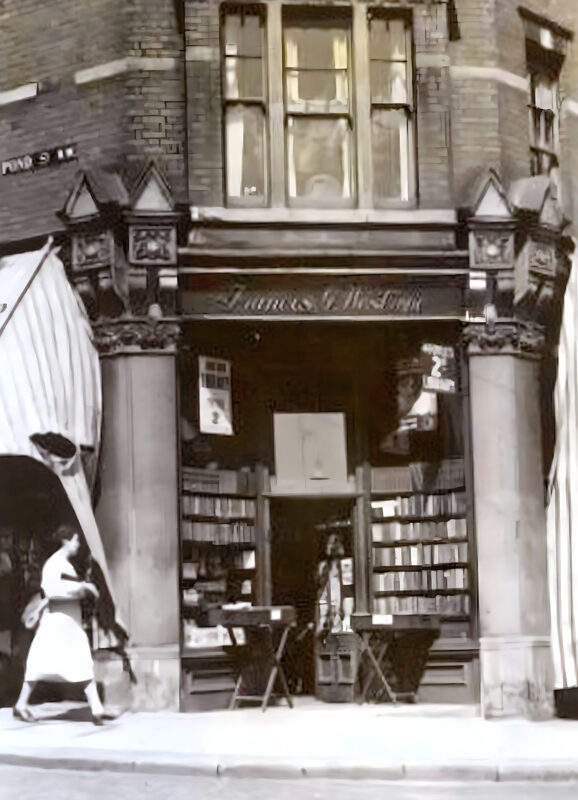

Grigson reviewed two books about Orwell with a ferocity familiar to his readers – in 1971 and 1980 – which provide several new pieces for the biographical jigsaw. We learn that Grigson was introduced to Orwell by Dylan Thomas – while browsing at Booklovers’ Corner in Hampstead in the mid-1930s – but also, that they first met as boys through a mutual friendship with the Perrycoste family. Grigson’s scathing attack on Orwell (the writer and the man), his intense dislike of Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four and scornful comments about Bernard Crick’s writing, makes for extraordinarily interesting reading.

Grigson read The World of George Orwell (1971) with “great curiosity” as Orwell was “an author whose books he did not like” and “whom he did not find very attractive in himself” describing him as as a “long, grey, and a kind of sideways man”:

I have to convict myself, and say that unlike a million or two readers, I never brought myself to finish Animal Farm or Nineteen Eighty-Four, repelled partly by the quality, or absence of quality, in the writing. So I prepared myself in a perhaps penitential way for reading eighteen essays about him, some by friends, some by admirers, or admiring critics, one or two in which the attitudes are more ambiguous, one at least which is downright hostile—essays with a commentary in photographs divided between Orwell personally and the times and circumstances round him.

Grigson makes no mention in this review of Cornwall or Eric Blair as a boy. It will be nine years before that penny drops while reading Bernard Crick’s biography of Orwell!

It is interesting that he concludes this first review with a strangely paradoxical comment possibly suggesting he is open to re-appraising Orwell’s work more positively:

Yes, a kind of saint, hunting truth, finding something to approve in the beastly, and something beastly in the approved; appealing to the leftness in the people of the right, and the rightness in the people of the left. “A confused and divided man”; yes, but one who held up the concealed home-truths…

before asking the barbed questions:

Isn’t he a kind of Swift or Voltaire without art? Even a Cobbett without art? And if one says “without art,” is one leaving so very much behind?

Grigson’s review of Crick’s, Orwell: A Life (1980) is worth examining in more detail. He opens by saying that, “George Orwell, in childhood Eric Blair, was a paradoxical creature, an extra odd kind of invisible man who left strong footmarks on the flower-bed, and knocked off the hats (we used to wear hats, after all) of Smugness and Hypocrisy when they expected least to have to go bareheaded and reveal their spiritual dandruff or baldness, or worse…”. Considering the influence of the Perrycoste family and their expertise in local flora, “left strong footmarks on the flower-bed” is a notable phrase.

There is trenchant criticism of the biography throughout the review but Grigson does say, “having known and observed first Eric Blair, then George Orwell” that he did not find himself “very much disagreed with the figure disentangled and illuminated by Professor Crick”. By Grigson’s standards, this is very high praise indeed. The reviewer was certainly excited by the third chapter:

When I was young and living in Cornwall near Polperro, I had two friends—Honor and Bernard Perrycoste—and there they were, names and (mis-spelt by Professor Crick), picnic and bathing friends of Blair’s in the summer before mine. I once too had known this Eric Blair. But I had never had cause to remember him. I had forgotten that he was called Eric Blair, I had forgotten the encounter, until, last week, there he was at Polperro and Looe, on page 35 in Bernard Crick’s third chapter, called up—after about 60 years—an under-exposed time browned mental picture of a skinny boy, I think on the beach at Lansallos, wearing one of those loose, shoulder-to-thigh bathing dresses which everyone wore.

The walk to Lansallos Beach must have been a familiar one for Orwell and the Perrycoste family.

Grigson explains why he did not immediately make the connection between the writer he met in the 1930s with the “skinny boy” of his youth:

I suspect I had forgotten this boy so thoroughly, never connecting him with Eric Blair or George Orwell, because he was so self-effacing. Twenty years later Dylan Thomas was to describe him to a known, not-too-famous writer as “the invisible bookseller” when he worked in Hampstead. This time I met the invisibility, and his self-effacement, his sidelong glance among the shelves, the morose gentleness in what he said and the way he said it, his voice trailing to an almost embarrassed and embarrassing silence.

I do not know who the “not-too-famous writer” was that described Orwell as “the invisible bookseller” to Thomas. Your thoughts?

Grigson lists the many writers who resided in the neighbourhood and offers some commentary on Orwell’s friendships:

It was always as if George Orwell, afraid of not impressing others (including women), could not impress himself. Hampstead—and that area of Hampstead near Keats Grove and Orwell’s bookshop—was then extraordinarily full of eminence in esse and rather more than in embryo. Henry Moore, Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, John Summers, Edwin Muir, Paul Nash, Louis MacNeice, Herbert Read and many more lived a few hundred yards off the bookshop, but few appear in Professor Crick’s chapters, or in Orwell’s life.

I think he preferred friendship with the second-rate or the third-rate, as if afraid, as if he could perfect his reticence and keep his pride, being sceptical, as he must have been, about the very many third-raters Professor Crick has had to call on or trust to for evidence and reminiscences, was neither here nor there.

It would be wrong, though, to estimate Orwell by his friends, just as it would be wrong to estimate his importance by the frequently slapdash and illiterate way his biographer writes about him. For judgments on literature I would not go to a writer or a biographer who had to write in English so weak as Professor Crick’s (whose forte is political science). It does not do to talk of Orwell as a great writer. He was a grey writer, trenchant but grey, and I cannot accept that Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm are great literature. It does do—and Professor Crick does it—to insist on Orwell’s fierce vision of the necessity of truth, on his dread, in his words, “that the very concept of objective truth is fading out of the world”.

Grigson concludes with a jab at Crick, saying the text needs “combing for all sorts of minor errors about people and other small felicities”. He also claims the “best thing in this biography” is the quote from V. S. Pritchett, that Orwell was “the wintry conscience of a generation”.

Reflection

Grigson’s own life as a critic, poet, employee of the BBC and his personal connections to Orwell make him an interesting and previously unknown source. His turn-of-phrase and genuine talent for descriptive writing makes his commentary about Orwell in these reviews both engaging and thought-provoking.

More work is also needed on the period Orwell worked at Booklovers’ Corner. Did any of the writers listed by Grigson as residing nearby the bookshop write letters or diary entries about Orwell? I’d guess that they did not do it at the time but possibly, after Orwell became more well-known, or on his death, some made passing comments about those days in the mid-1930s? Contextually, his politically active employers, Francis and Myfanwy Westrope, who were Esperantist friends of Orwell’s aunt Nellie Limouzin are also worthy of more research.

One wonders where other texts may be found which illuminate the world of the Perrycoste family and the experiences of a young Eric Blair during those lost summers in Polperro over a century ago.

REFERENCES

Crick, Bernard (1980) George Orwell: A Life,

Ferris, Paul, Dylan Thomas: A Biography, New York: Paragon House Publishers, 1989

Fryer, Jonathan, Dylan: The Nine Lives of Dylan Thomas, London: Kyle Cathie Ltd., 1993

Grigson, Geoffrey, The Crest On The Silver: An Autobiography, London: Cresset, 1950

Grigson, Geoffrey, Recollections, Mainly of Writers & Artists, London: Chatto & Windus, The Hogarth Press, 1984

Grigson, Geoffrey (1971) ‘An Agonising Reappraisal – The World of George Orwell’, Country Life, Oct 14.

Grigson, Geoffrey (1980) ‘A Fierce Vision: George Orwell: A Life’, Country Life, Dec 25.

Gross, Miriam (ed), The World of George Orwell, Weidenfield and Nicholson, 1971

Orwell, George (1998) A Kind of Compulsion: 1903-1936, The Complete Works of George Orwell – Volume 10, Secker & Warburg

Symons, Julian. “Grigson, Geoffrey Edward Harvey (1905–1985), poet and writer.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004; Accessed 5 Aug. 2023. https://www-oxforddnb-com.ezproxy.sl.nsw.gov.au/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-31176

Acknowledgments

Sincere thanks to Nick Childs for the photos of Lansallos Beach and to Stephen Buckley who provided excellent leads a few years ago!

Discover more from Darcy Moore

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Unkle Cyril

What a character Grigson must have been.

Sue B

Great research presenting an interesting take on Orwell. Leaves the reader questioning some recent publications.