The 80th anniversary of the publication of George Orwell’s novel has been celebrated this week from a range of perspectives in the mainstream media. Richard Blair wrote an article in The Guardian and The Orwell Society published a number of posts at the website by members.

What follows is some less well-known insights into the publication of the novel.

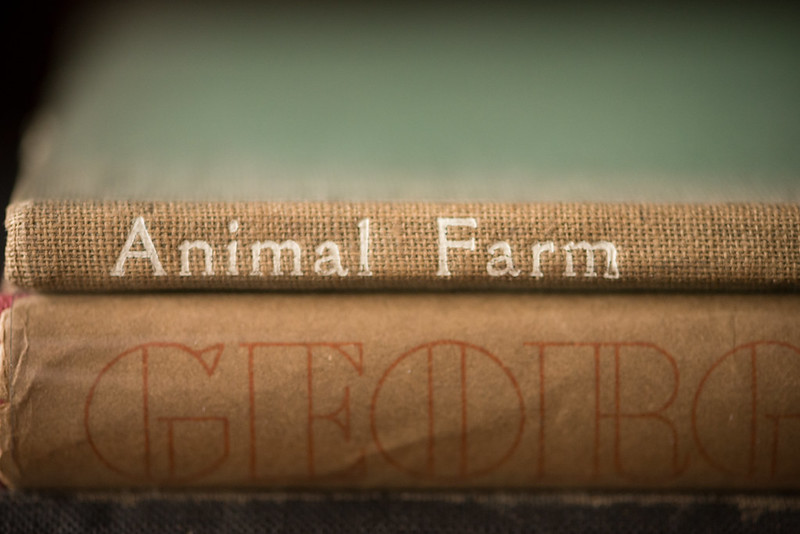

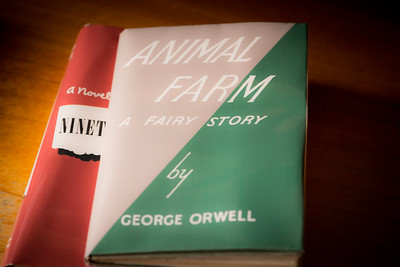

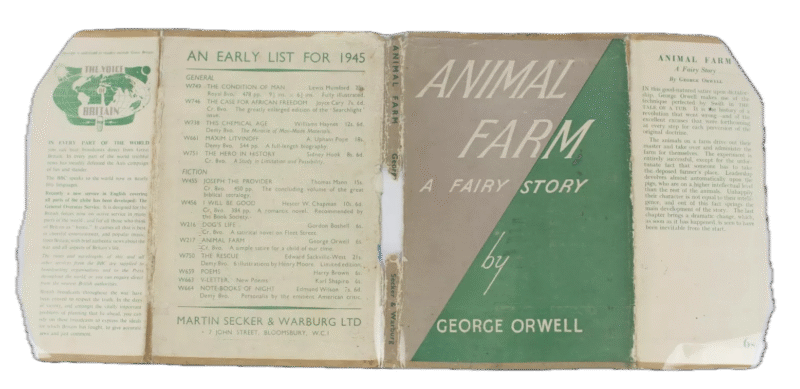

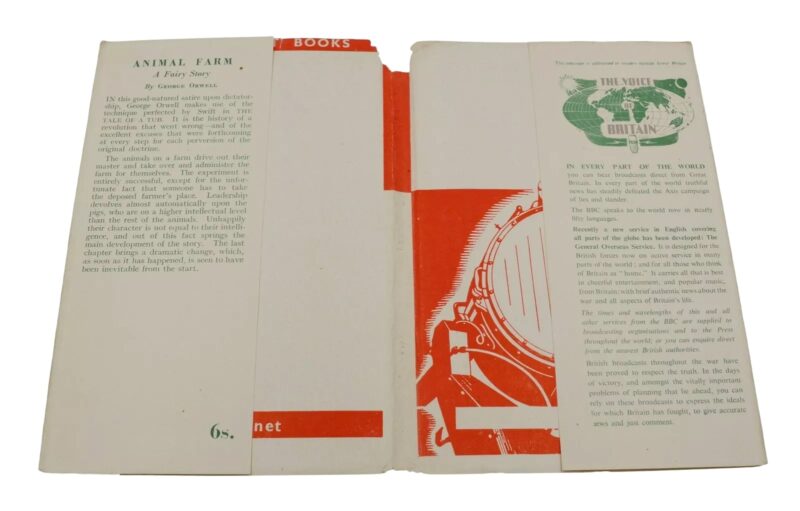

Animal Farm was published in London by Secker & Warburg on the 17th August 1945 and in New York one year later. I am fortunate to own one of the first print run of 4,500 copies which sold out in six weeks. This edition is very fragile due to publishers complying with the Book Production War Economy Agreement.

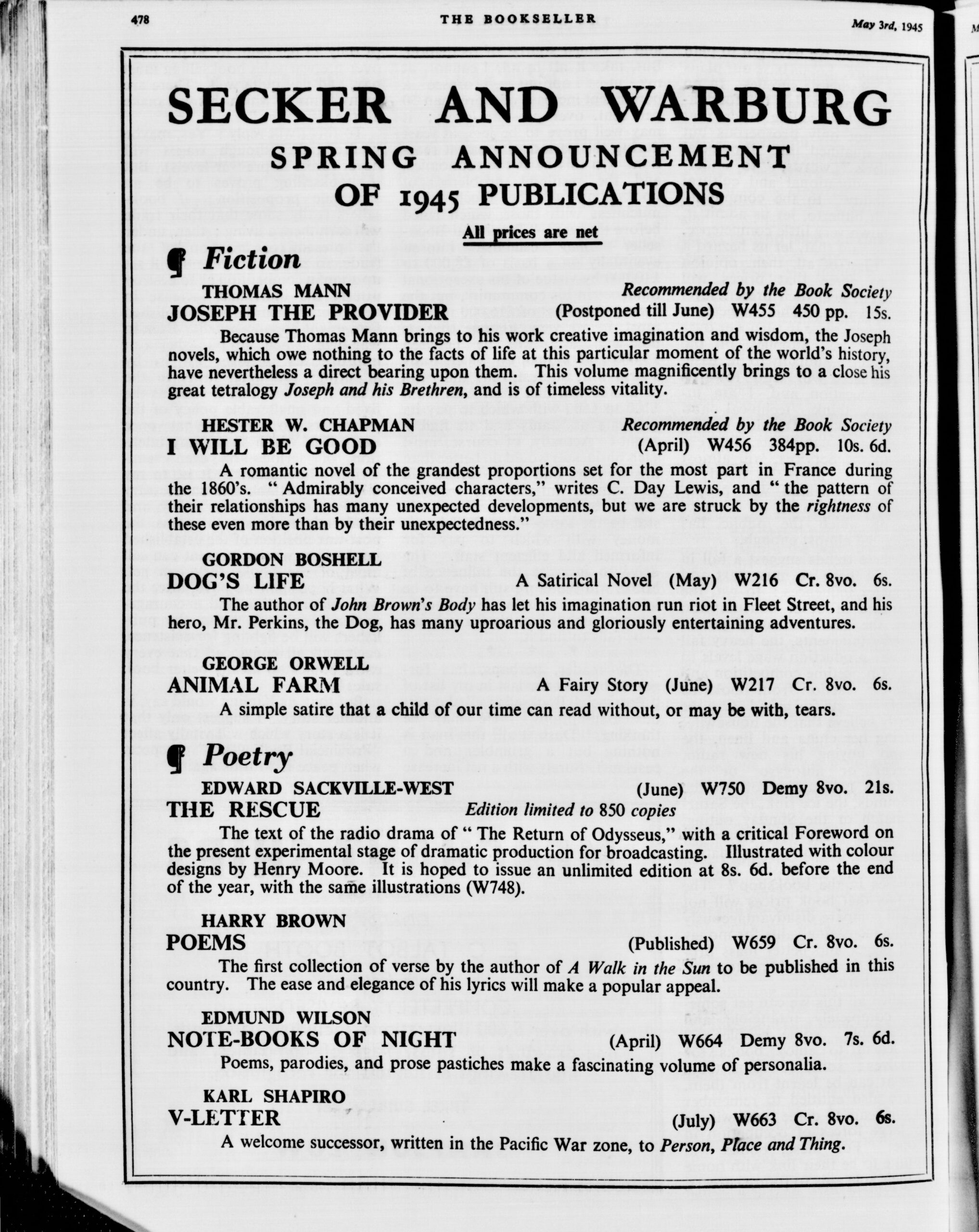

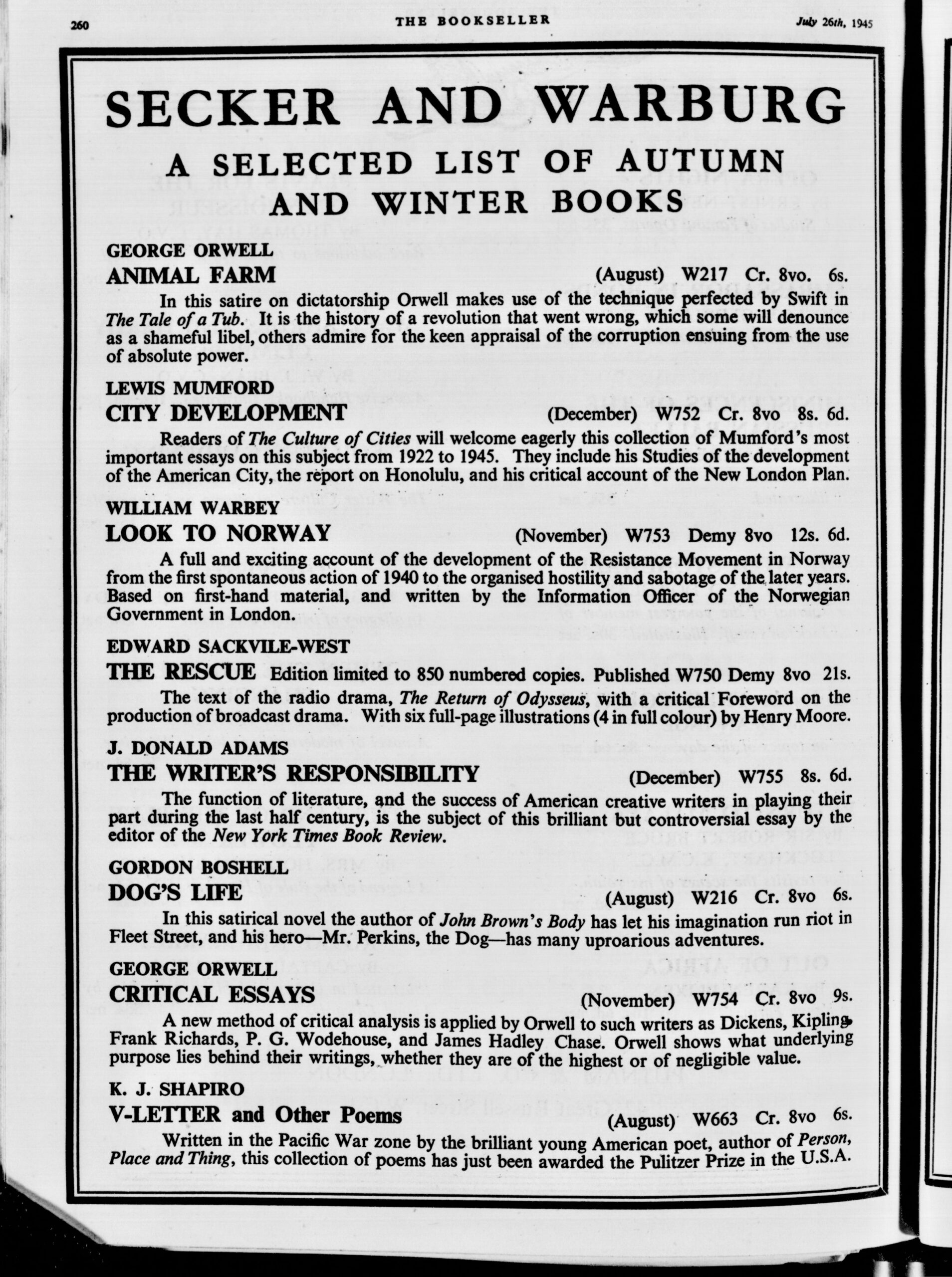

On the 3rd May 1945, Secker & Warburg originally advertised in The Bookseller that Animal Farm would be published in June. Their next advert, on 26th July, announced the imminent release of Animal Farm and Critical Essays (which was delayed until the following year).

When I open my first edition of the novel, the copyright page reveals the book was “First published in May 1945”. However, the shortage of paper led to a delay in production and the novel was not available on the shelves until more copies were printed in early August.

The scrabble for paper was indeed a desperate one. The very fragile dust jacket was made from recycled material as evidenced by the advertisements for Searchlight Books on the verso.

The other odd thing is that this British first edition commences on page 9. Orwell’s introduction, The Freedom of the Press, was removed at the last moment. It was later translated for the Ukrainian edition of the novel and did not see the light of day In English until published in the Times Literary Supplement during 1972.

The Sydney Morning Herald

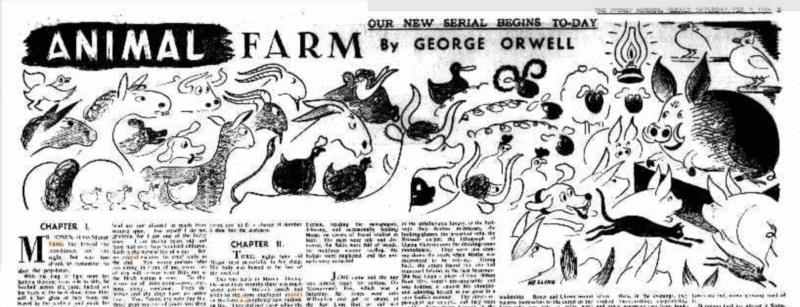

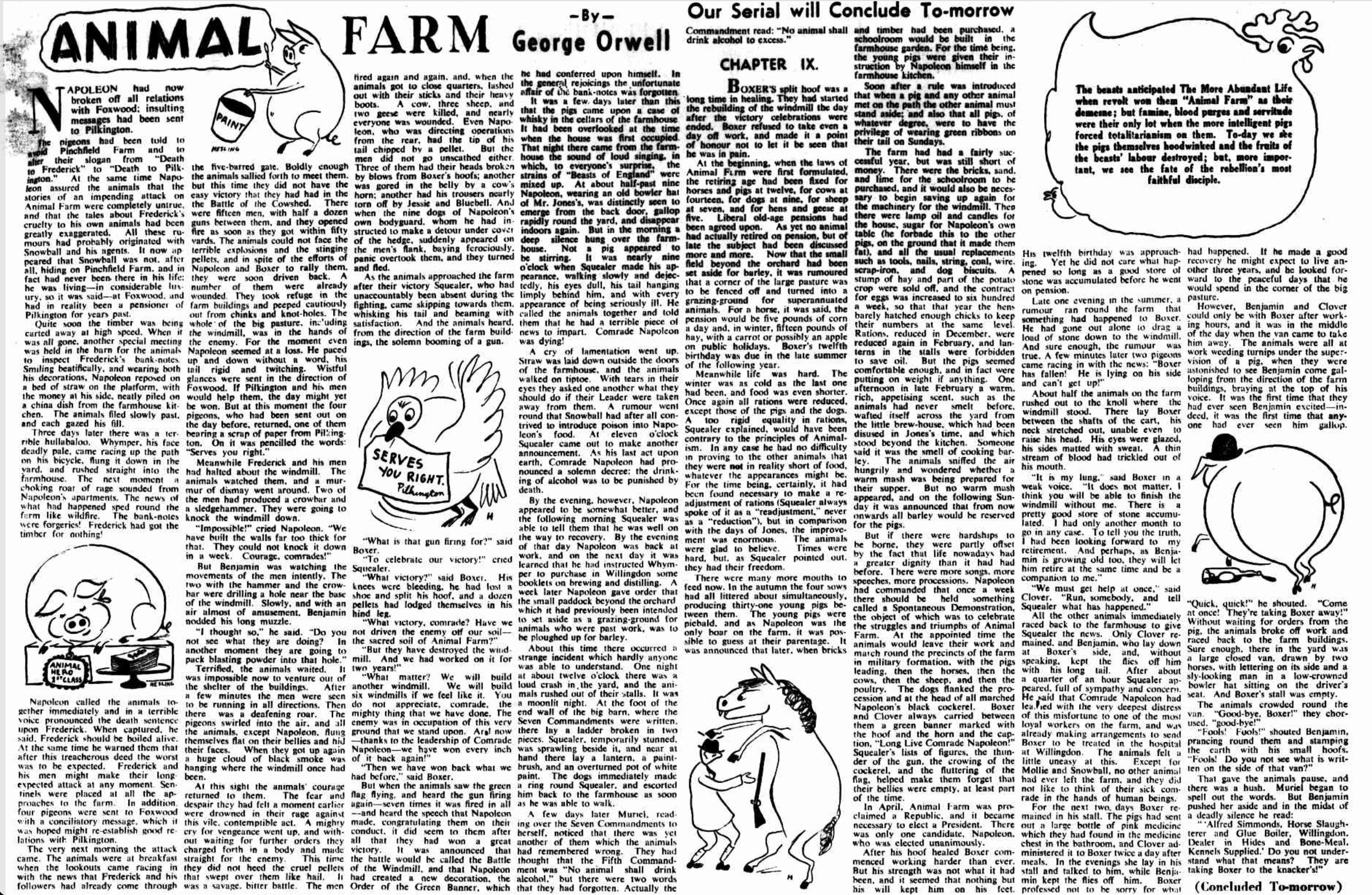

In between the first UK publication in August and the American edition a year later, the novel was serialised in Australia.

Animal Farm was published in the Sydney Morning Herald on 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15 February 1946. Orwell wrote to his agent, after being sent press cuttings remarkably quickly. It is easy to see why he was not overly enthusiastic about the illustrations by Bernard Hesling (1905-1987) being used in a future edition of the novel, although he does say he thinks “they are quite good”:

23 February 1946

27 B Canonbury Square

Islington London N1

Dear Mr Moore,

Many thanks for the cuttings from the Sydney Morning Herald, which I return herewith. I think they are quite good, but I don’t think they are quite the kind of thing that would be worth incorporating in a book if it were ever decided to do an illustrated edition of “Animal Farm.” I’ll talk this over with Warburg again. I suppose the book will be re-issued some time, and certainly it would be nice to have it illustrated. There was some vague idea of Low doing it, as according to Horrabin he (Low) once remarked he would like to do it. But I don’t suppose that will come to anything, and I dare say some time I’ll run across some young artist whose style would be suitable.

![]()

All Fairies Are Equal

Eileen Blair, Orwell’s first wife, collaborated in the planning and drafting of Animal Farm. On the 19th February 1946, Orwell wrote to Dorothy Plowman acknowledging Eileen helped to plan the novel:

“My book ‘Animal Farm’ has sold quite well, and the new one, which is merely a book of reprints, also seems to be doing well. It was a terrible shame that Eileen didn’t live to see the publication of “Animal Farm,” which she was particularly fond of and even helped in the planning of. I suppose you know I was in France when she died. It was a terribly cruel and stupid thing to happen. No doubt you know I have a little boy named Richard whom we adopted in 1944 when he was 3 weeks old. He was ten months old when Eileen died and is 21 months old now. Her last letter to me was to tell me he was beginning to crawl.”

Each evening they read through the drafts together in bed. All of Orwell’s biographers acknowledge Eileen’s central importance in his life and work, especially Animal Farm:

“One cannot emphasise too strongly the importance of Eileen O’Shaughnessy, in the life of Eric Blair, and hence, of George Orwell – indeed, her entrance into his life would hasten the transformation.” Peter Stansky (1979)

“It was this slightly mischievous sense of humour which attracted Orwell to her in the first place. She could appreciate his dry wit, and she was capable of matching it with her own quips. She was not intimidated by him, and she was not the kind of woman whom he could easily shock with his unconventional remarks. She was also one of the most intelligent women he would ever meet, and he was well aware of it. Having read widely in English literature, she could hold her own with him in discussions about poetry or fiction. And as her surviving letters show, she was an excellent writer, with a strong sense of style. Her friends thought that Orwell’s marriage to Eileen was, among other things, beneficial to his writing. They believed that she was a perceptive critic and influenced the development of his style by reading his works while he was in the process of writing them, and giving him her honest opinions.” Michael Shelden (1991)

One opinion piece writer has recently posited that:

“It’s impossible to know which of Eileen or George came up with the famous line: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others”. What’s certain is that it was meant as a criticism of inequality.”

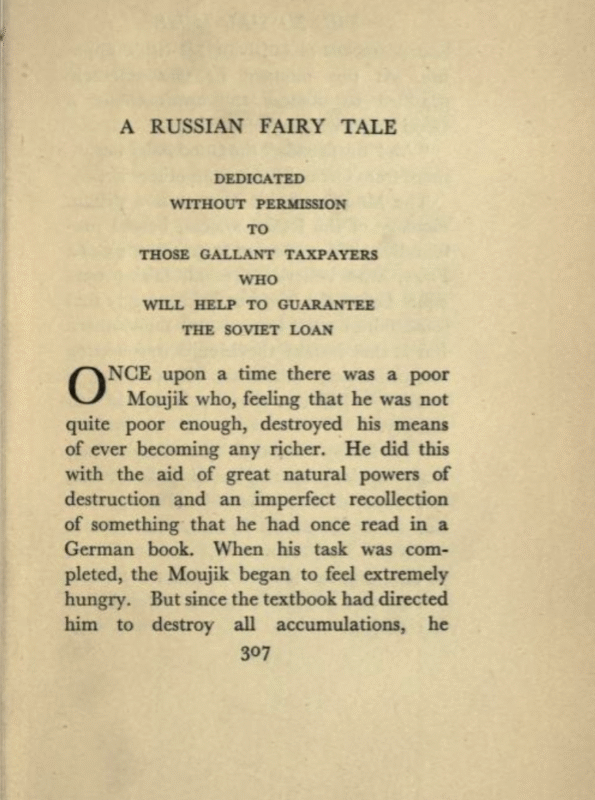

However, it is pretty well-accepted, although not well-known, that Orwell likely appropriated the idea from The Missing Muse & Other Essays (1928). This book by Philip Guedalla (1899-1944) has the following lines:

“The Moujik, unable to repress a distant memory of the feudal system, bowed profoundly. This appeared to gratify the Good Fairy, who believed that all fairies were equal before the law, but held strongly that some fairies were more equal than others. But at that instant the Moujik, recollecting his principles, called the Good Fairy a number of bad names…”.

Orwell would have likely come across this book when he worked at Booklovers’ Corner in the 1930s. A modicum of scholarship reveals that the famous epigram had a prehistory. Ironically, this was pointed out by the feminist scholar, Daphne Patai, a stern critic of Orwell’s, over forty years ago when she referred to a review by Richard Mayne.

As an aside, I was vastly amused by Guedalla’s comment in another book:

“BIOGRAPHY, like big game hunting, is one of the recognised forms of sport; and it is as unfair as only sport can be. High on some far hill-side of politics or history the amateur marks down his distant quarry. Follows an intensely distasteful period of furtive approach to the subject, which leads the deer-stalker up gullies and ravines and the biographer through private letters and washing-books. The burns grow deeper and wetter, the letters take a more private and a less publishable turn, until at last our sportsman, well within range, turns to his publisher, who carries the guns, and empties one, two, and (if the public will stand it) three barrels into his unprotesting victim ; because it is a cruel truth that the subjects of Lives are rarely themselves alive. It is at once the shame of biographers and the guarantee of their marksmanship that they are perpetually shooting the sitting statesman.”

Concluding Thoughts

Who knows where an author pulls his ideas from in the creative process of writing a novel. Orwell was a close observer of nature and we can see his affinity with animals throughout his work and life. Ansell Adams believed that “all the pictures you have seen, the books you have read, the music you have heard, the people you have loved” were employed in the process of making a photo! Any close study of Orwell’s novels, with this philosophy in mind, bears fruit.

Widely read and travelled, Orwell had been preparing to become a writer since his youth. He particularly enjoyed the humorous satirical lashings provided by Jonathan Swift and Animal Farm, which owes much to Swift, is Orwell’s most perfect novel! It is the book which resulted in him becoming that “FAMOUS AUTHOR” he had dreamt about as a boy with Jacintha Buddicom.

It is hard to believe that T.S. Eliot rejected the novel for Faber with the now infamous assertion:

“And after all, your pigs are far more intelligent than the other animals, and therefore the best qualified to run the farm – in fact, there couldn’t have been an Animal Farm at all without them: so that what was needed (someone might argue), was not more communism but more public-spirited pigs.”

Speaking of pigs, one treasure in my library is a book inscribed to the late Ian Angus by Jacintha Buddicom. It reveals Orwell’s love of another fable – “one of his favourites” – The Tale of Pigling Bland.

REFERENCES

Discover more from Darcy Moore

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Michael Casey

I enjoyed the read of this very much. I did read the Pigling Bland book and found it ah not very good.