“Academic writing was actually about hiding what you didn’t know. There was a language, a technique, and I had mastered it. In everything there were gaps which language could cover over as long as you had acquired the know-how. I had, for instance, never read Adorno, knew practically nothing about the Frankfurt School, just the snippets I had picked up here and there, but in an assignment I could manoeuvre the little knowledge I actually had in such a way as to make it appear greater and more comprehensive.” Karl Ove Knausgaard

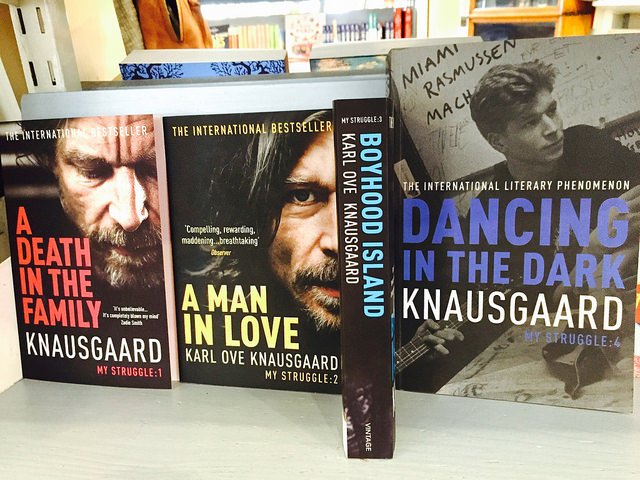

Some Rain Must Fall: My Struggle Book 5, by Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgaard, does not disappoint and I sped through it the week the English translation appeared. Karl Ove, in this instalment, is studying writing in Bergen and we follow his travails until he leaves this medieval city. As always, we see his wounds in macro close-up as he fails at writing, love, relationships and being a decent human being. It hurts the reader too. His insight and honesty are what has engaged so many who see their own lives writ small. His comments about ‘academic writing’ made me laugh aloud more than wince. That came afterwards.

.I wanted to write, that was all I wanted, and I couldn’t understand those who didn’t, how they could be happy with an ordinary job, whatever it was, whether teacher, camera operator, bureaucrat, academic, farmer, TV host, journalist, designer, promoter, fisherman, lorry driver, gardener, nurse or astronomer. How could that be enough? I understood it was the norm, most people had ordinary jobs, some put all their energy into them, others didn’t, but to me they seemed pointless. If I were to take such a job my life would feel meaningless however good I was at it and however high I rose. It would never be enough.

If all good books are about good books, or the process of writing them, Some Rain Must Fall passes the test. Reading is important to Knausgaard, almost as important as writing and this passage will stir something deep inside most people who pick up his book:

We were nobodies, two young lit. students chatting away in a rickety old house in a small town at the edge of the world, a place where nothing of any significance had ever happened and presumably never would, we had barely started out on our lives and knew nothing about anything, but what we read was not nothing, it concerned matters of the utmost significance and was written by the greatest thinkers and writers in Western culture, and that was basically a miracle, all you had to do was fill in a library lending slip and you had access to what Plato, Sappho or Aristophanes had written in the incomprehensibly distant mists of time, or Homer, Sophocles, Ovid, Lucullus, Lucretius or Dante, Vasari, da Vinci, Montaigne, Shakespeare, Cervantes or Kant, Hegel, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Lukács, Arendt or those who wrote in the modern day, Foucault, Barthes, Lévi-Strauss, Deleuze, Serres. Not to mention the millions of novels, plays and collections of poetry which were available. All one lending slip and a few days away. We didn’t read any of these to be able to summarise the contents, as we did with the literature on the syllabus, but because they could give us something.

Knausgaard is a great source for finding new reading material outside that of my usual anglo-centric reading habits and I have been tracking down Norwegian writers to pursue; Tor Ulven‘s only novel, Replacement, is winging its way to me as I type. There are quite a few lists, like this one, throughout the work:

Norwegian literature?’ he said. ‘Bit of everything,’ I said. ‘Kjærstad, Fløgstad, Jon Fosse. All sorts of books really. What about you?’ ‘A broad range too. But Øyvind Berg is good. Tor Ulven is fantastically good. Ole Robert Sunde, have you read anything by him? A whole novel about the main character, who walks to a kiosk and back. Odyssey, right?

Knausgaard writes about Knausgaard so it probably makes sense to hear the author talking about this book in this 3-4 minutes excerpt from a recent interview. His comments about his relationship with his brother are particularly interesting (there is a minor spoiler).

Spending a week or so in Bergen a couple of years ago deepened my enjoyment of Knausgaard’s book. The title partly refers to the incredibly high rainfall the city experiences although we had blue skies for the whole time we visited, except for one downpour. As always, having that mental picture of the setting seems to make the story one the reader participates in more completely. One can know what a funicular is but having travelled, to overlook the city, in the Bergen one feels satisfying while reading. We had a loft apartment overlooking the medieval city and harbour.

flickr photo shared by Darcy Moore under a Creative Commons ( BY-NC-SA ) license

I would highly recommend starting the first book of My Struggle today in preparation for the final instalment. It is unputdownable.

“The chief task of philosophy in all ages has consisted precisely in finding the connection that necessarily exists between personal and common interests.”

The recent BBC adaptation of Leo Tolstoy’s magisterial, War and Peace, which I read and loved quarter of a century ago, led me to finally tackle Anna Karenina. I enjoyed this novel in bursts, often finding the domestic situations it describes tedious and was on the verge of throwing it aside several times when some insight or other would sweep me back into the story.

The quote above, from the novel, is at the very heart of Tolstoy’s appeal as a novelist. He is a philosopher of the everyday, interested in reconciling the personal with public weal and his long-life, observing many facets of Russian life and society, gave him a deep reservoir of material and experiences.

Tolstoy mostly creates engaging characters who grow and change, often unexpectedly. Liked would not be the right word but Levin and Vronsky are interesting characters. I did not enjoy Levin’s arc of development and noted it paralleled Tolstoy’s religious conversion. Anna seemed strangely distant from the narrative and I also found Dolly and Kitty irritating. Vronsky’s character surprised me as I found him dull at first but I guess others would have seen him as Byronic from the beginning.

“Vronsky meanwhile, despite the full realisation of what he had desired for so long, was not fully happy. He soon felt that the realisation of his desire had given him only a grain of the mountain of happiness he had expected. It showed him the eternal error people make in imagining that happiness is the realisation of desires.”

“And as a hungry animal seizes upon every object it comes across, hoping to find food in it, so Vronsky quite unconsciously seized now upon politics, now upon new books, now upon painting.”

Tolstoy is a particularly good aid for any reader’s emotional intelligence, as are all good novels. His ruminations on marriage, desire, death, philosophy, farming, class, society and a host of political issues are deeply interesting and wise. Levin’s love of working, side by side with his farmhands, is particularly well rendered and close to Tolstoy’s heart. Often one is surprised by the clarity with which an idea or emotion is represented and comforted to see a familiar thought appear. Knowing it was written some 150 years ago deepens the pleasure as one thinks about how many people must have read, and felt, the same passages since Tolstoy originally published the story in serial form.

Tolstoy, like Shakespeare, who he criticised savagely*, does not need his first name such is his literary importance. Having said that, Tolstoy always seems quite mad to me for such a giant of world literature (how could he think Shakespeare ‘ordinary’ and not like King Lear?). His journey, from young aristocrat to peasant christian anarchist, would have been quite unique, one would imagine. It certainly provided fodder to people his novels and perhaps understand how 19th century Russia became communist in the 20th century. Tolstoy would have felt applauded some of the political revolutions but been horrified with the attacks on religion, purges and gulags. Interestingly enough, Tolstoy’s novels never fell out of favour in Stalin’s Russia.

*Orwell responded brilliantly.

Anna Karenina is a doorstop and has taken two months to finish. I would certainly recommend War and Peace as essential but would hesitate to say this other Tolstoy is worth the effort to any but the most committed. It requires a little too much discipline for the rewards on offer. However, I feel virtuous for finishing it. I do wonder about the impact of gender on reader appreciation of the novel. Do female readers prefer this Tolstoy to his other fictions?

Russian Literature: A Very Short Introduction is a great little read (about some great, lengthy books) by Catriona Kelly. She does not take a traditional, chronological approach to an introductory survey of such a topic but explores Russian writing thematically. It was not what I expected but is certainly an interesting read. I did find myself not wanting to know any more about Alexander Pushkin though. It did make Tolstoy more contextually rewarding to be traversing the field as I read Anna Karenina.

I plan to read more Russian literature starting with the fiftieth anniversary edition when it is released in May of The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov, translated Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. I also need to spend time with Dostoevsky.

.

A Russian Journal by John Steinbeck, with photographs by Robert Capa, made me remember how powerful and authoritative was Steinbeck’s voice in 20th century literature. Capa and Steinbeck travel to Russia in 1947 to report what they see, rather than analyse the politics of the period. Steinbeck is an honest exponent of genuine journalism and Capa could “photograph thought” so this is an important historical document as well as interesting read.

Steinbeck’s writing is spare and direct. The reader is really in the room, with an irritable Capa or a beautiful and serious young Russian guide. One laughs at Capa’s penchant for stealing books and the intellectual challenges set each morning by Steinbeck for his photographer friend. The people of Georgia, or the defenders of a factory, in Stalingrad, from the German assault are celebrated without being eulogised. He is master among masters.

Steinbeck is honest in a way that makes Knausgaard (I was switching between the two books) seem like a conjurer of cheap tricks in service of a narrative rather than the truth-teller he is purported to be. Steinbeck is the real deal and one senses, as in most writers who have experienced the tragedy of war firsthand, an authentic, no bullshit approach to his writing. The prose is all-important but only as a vehicle for transmitting truth.

There are many priceless observations to admire – especially when viewed from such a distance of time and history – throughout the journal. Not many are better than this more than generous piece of speculation about the new role of ‘the writer’ in Stalin’s Russia:

“Stalin may say that the writer is the architect of the soul, in America the writer is not considered the architect of anything, and is only barely tolerated at all after he is dead and carefully put away for about twenty five years. In nothing is the difference between the Americans and the Soviets so marked as in the attitude, not only toward writers, but of writers toward their system. For in the Soviet Union the writer’s job is to encourage, to celebrate, to explain, and in every way to carry forward the Soviet system. Whereas in America, and in England, a good writer is the watch-dog of society. His job is to satirize its silliness, to attack its injustices, to stigmatize its faults and this is the reason that in America neither society nor government is very fond of writers. The two are completely opposite approaches toward literature. And it must be said that in the time of the great Russian writers, of Tolstoy, of Dostoevski, of Turgenev, of Chekhov, and of the early Gorki, the same was true of the Russians. And only time can tell whether the architect of the soul approach to writing can produce as great a literature as the watch-dog of society approach. So far, it must be admitted, the architect school has not produced a great piece of writing.”

It was to become terrifyingly clear that the next Russian writer of distinction, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, would definitely fit into ‘the watchdog’ category.

You can see Capa’s photos here. One sense that many of them could have been taken in previous centuries without huge amounts of change. Scenes, on Levin’s farm in Anna Karenina, are not far from my mind when viewing these.

The beehives of the collective farm.

.

As a teenager, my first Steinbeck was The Pearl – a parable about corruption and capitalism very suitable for younger readers – which had a deep and lasting effect on me. I have read several of his novels most oft prescribed for English courses but am looking forward to reading some of the lesser known works. The Red Pony is on the top of my pile.

“Imagine that the genome is a book. There are twenty-three chapters, called CHROMOSOMES. Each chapter contains several thousand stories, called GENES. Each story is made up of paragraphs, called EXTONS, which are interrupted by advertisements called INTRONS. Each paragraph is made up of words, called CODONS. Each word is written in letters called BASES.” Matt Ridley

Genome: the Autobiography of a Species in 23 Chapters is an ingeniously structured book and has been more than merely helpful in my ongoing quest to learn more about genetics and DNA prior to traveling to the USA next month where I will meet some leaders in the field of non-medical DNA analysis.

Matt Ridley’s approach to popular science really worked for this non-scientist. Each chapter is devoted one pair of chromosomes; you may wish to see an overview. I listened to the audiobook and found myself re-playing many passages to deepen my understanding of the content and enjoy the writing. Here’s an example:

“The fuel on which science runs is ignorance. Science is like a hungry furnace that must be fed logs from the forests of ignorance that surround us. In the process, the clearing we call knowledge expands, but the more it expands, the longer its perimeter and the more ignorance comes into view.”

I felt occasionally that Ridley was pushing personal hobby-horses and strays a little from scientific fact into the realm of opinion about some issues, especially intelligence and personality. Mostly though, he seems sage and one would not imagine that a book written well over a decade ago would still be highly recommended in this field of science but it still appears popular and oft read.

Highly recommended.

“In most households, you’d have had variations on this discussion: ‘Hey, Mum, good news – I scored 99 out of 100 in the French test.’ ‘Oh, what a shame. You’d better work on the word you messed up.’ ‘I also got 99 out of 100 for mathematics.’ ‘That’s why you should have studied harder the night before. And don’t use the word “got”; “received” is better.’ ‘Well, Mum – what about this? I received 100 out of 100 in history.’ ‘Don’t brag, darling. It’s not nice.” Richard Glover (in conversation with his mother)

Flesh Wounds by Richard Glover starts engagingly, slows and one almost throws away the book before it recovers to become a really interesting memoir. His tales of childhood were amusing, as is his self-deprecating take on his own character, especially in his teenage period of being an intellectual. His descriptions of the lovelessness of his mother would be self-pityingly harsh except for Glover’s sense of humour. One can feel the pain though.

I particularly appreciated Glover’s ability to re-evaluate his judgement of his parents, especially his mother, in a manner that broadens our own appreciation of who he has become and the paradox inherent in their characters. Glover’s life in England and the process of tracking down long-lost relatives is also interesting as part of his literal journey to understand why his mother dissembled, on such an enormous scale, about her own origins.

Flesh Wounds is worth a read.

What have you been reading?

Featured image: flickr photo of Tolstoy in his study by Tschäff https://flickr.com/photos/tschaff/336845534 shared under a Creative Commons (BY-SA) license