“We have been systematically misinformed about what depression and anxiety are.” Johann Hari

“Mental health is produced socially: the presence or absence of mental health is above all a social indicator and therefore requires social, as well as individual, solutions.” World Health Organisation

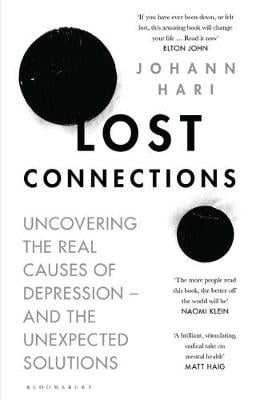

An article in The Guardian led me to read Lost Connections: Uncovering the Real Causes of Depression – and the Unexpected Solutions by Johann Hari. Hari examines the research, talks with experts and makes some workable suggestions for how we can improve the wellbeing of individuals and our communities generally. The author’s thesis, that those feeling depressed or anxious are not machines with malfunctioning parts but beings with unmet human needs, resounded with this reader and seems terribly obvious.

Ironically, learning that depression and anxiety are not caused by a chemical imbalance made me feel unbalanced.

Hari took anti-depressants for thirteen years. He was told that he had a “chemical imbalance” and that the medication would assist to normalise his outlook. His research into the causes of depression made him realise that the focus of his doctors was a narrow one. He starts to understand that there are biological, psychological, and social causes for depression and none of these three can be described by something as crude as the idea of a chemical imbalance. He posits that social and psychological causes have been ignored for a long time, even though it seems “the biological causes don’t even kick in without them”. He draws the conclusion that:

Giving people drugs for depression and anxiety is one of the biggest industries in the world, so there are enormous funds sloshing around to finance research into it (and that research is often distorted, as I learned). Social prescribing, if it is successful, wouldn’t make much money. In fact, it would blast a hole in that multibillion-dollar industry.

The contents page in Hari’s book clearly lists nine causes of depression. Many of these are particularly devastating for young people, who have no or very limited power to fix family or societal problems. Immanuel Kant’s three simple rules for happiness are worth keeping in mind when reading through Hari’s list of causes: something to do; someone to love; and, something to hope for.

More importantly, Hari also outlines the potential ways that individuals can be reconnected to ameliorate depression and anxiety. The suggestions related to helping others resound. Reconnecting with nature is also particularly important. A decade ago I read Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children From Nature-Deficit Disorder and agreed with the sentiments expressed. More recently authors, including Margaret Atwood and Robert Macfarlane, have railed against the elimination of nature words from a children’s dictionary. Academic papers suggest that children’s “roaming radius” from home had shrunk by 90% in 30 years. Here’s Hari’s full list of what helps:

More importantly, Hari also outlines the potential ways that individuals can be reconnected to ameliorate depression and anxiety. The suggestions related to helping others resound. Reconnecting with nature is also particularly important. A decade ago I read Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children From Nature-Deficit Disorder and agreed with the sentiments expressed. More recently authors, including Margaret Atwood and Robert Macfarlane, have railed against the elimination of nature words from a children’s dictionary. Academic papers suggest that children’s “roaming radius” from home had shrunk by 90% in 30 years. Here’s Hari’s full list of what helps:

Hari’s analysis in Lost Connections echoed my professional experience working with young people and their families. As an educator, it has always been essential to have a holistic understanding of the challenges for those experiencing “mental health” issues and Hari’s call for a “new approach” resounded with this reader. In an era when many parrot the need for taxpayer dollars to be spent based on evidence-based solutions, a national approach is needed that genuinely looks at the individual in the larger context of how our society actually functions. That conversation is about a great deal more than the important topic of “mental health”.

Schools are often seen as “frontline services” and more is expected from educators as society becomes increasingly complex. Families do not always have the resources to cope with challenges of poverty, ill-health and issues that arise unexpectedly, especially if there are other huge pre-existing challenges. “Depression” and “anxiety” are the two words most likely to be spoken by students and parents in describing their challenges. For many years, talking with medical professionals re: student wellbeing, it has been clear there is not a holistic approach taken by policymakers towards educating young people and their families about managing mental emotional health and wellbeing. There has been a distinct lack of leadership and piecemeal solutions.

Youth suicide and cyberbullying has focused some in government to have a dialogue with organisations like Headspace but the larger societal issues that contribute are rarely connected. Young people have increasingly casualised and part-time work. Tertiary education is prohibitively expensive and the housing market is no longer in reach of a generation of Australians without permanent employment. The education system is increasingly caste-based. Some suburbs have near 100% of students in well-funded, expensive private schools and other areas of Sydney have the reverse. Australia has privatised education unlike any comparative country in the OECD. There is no need to quote/reference any of the points in this paragraph as they are so often discussed in newspapers and written about generally there should be no surprise. Of course, all is ideological and three decades of market-based policies have deeply-impacted on society.

The balance is not between the individual making good personal choices and societal support mechanisms but one of society providing equitable opportunities for citizens. The rat-eat-rat world of fast capitalism is impacting on the most basic tenets of civil society. Young people are the most vulnerable. Good health outcomes require holistic thinking and action. Leaving it to the market is fraught.

Hari references the impact of political, ideological change in Great Britain:

When I was a child, Margaret Thatcher said, “There’s no such thing as society, only individuals and their families”—and, all over the world, her viewpoint won. We believed it—even those of us who thought we rejected it. I know this now, because I can see that when I became depressed, it didn’t even occur to me, for thirteen years, to relate my distress to the world around me. I thought it was all about me, and my head. I had entirely privatised my pain—and so had everyone I knew.

He also lists how this ideology has impacted on the individual:

You are an animal whose needs are not being met. You need to have a community. You need to have meaningful values, not the junk values you’ve been pumped full of all your life, telling you happiness comes through money and buying objects. You need to have meaningful work. You need the natural world. You need to feel you are respected. You need a secure future. You need connections to all these things. You need to release any shame you might feel for having been mistreated.

Hari has been challenged on his findings in this book but it is acknowledged that much of what he presents is not likely to be seriously contested and “is well-known already”. The question must be, well-known to whom? The growing number of people who are prescribed medication? Politicians responsible for economic, social and health policy? Those who work with young people?

Hari has had good success with a TED talk and a previous book about drug addiction. He has had a mixed career in journalism being involved in a well-publicised case of plagiarism. Hari was stripped of his 2008 Orwell Prize for his ethical breach and the judges suggested he donate the prize money to English PEN. One would imagine he has learnt great deal from these professional challenges. Hari’s book is more than worth your time. I’d encourage you to read it doing as he suggests:

“As you read this book, please look up and read the scientific studies I’m referencing in the endnotes as I go, and try to look at them with the same skepticism that I brought to them. Kick the evidence. See if it breaks. The stakes are too high for us to get this wrong.”

My 14 year old daughter sent me the following witticism (currently doing the rounds online). It seems particularly pertinent to share to conclude this brief review:

Other titles read during January

Reservoir 13 (2017) by Jon McGregor

Go, Went, Gone (2017) by Jenny Erpenbeck

The Dark Is Rising (1973) by Susan Cooper

The Lost Words (2017) by Robert Macfarlane, Jackie Morris

Between the Bullet and the Lie: Essays on Orwell (2017) by Kristian Williams

George Orwell and the Radical Eccentrics: Intermodernism in Literary London (2004) by Kristin Bluemel

George Orwell: The Road to 1984 (1981) by Peter Lewis

Orwell and Gissing (1997) by Mark Connelly

Down And Out: Orwell’s Paris And London Revisited (1984) by Sandy Craig

Journey to the East (1956) by Hermann Hesse

The Orwell Tapes, (2017) by Stephen Wadhams

Being a Writer: Advice, Musings, Essays and Experiences From the World’s Greatest Authors (2017) by Travis Elborough, Helen Gordon

New Grub Street (1891/2017) by George Gissing

David Norris

Your commentary on Hari’s Lost Connections is well written and thought through. Very readable, relevant and important. Especially the comments about the destructive nature of Capitalism. Thank you for sharing your thoughts. I’m always enjoy your posts and am impressed by how much you read!

Depressed, lonely or both? – NewsVineWA

[…] Hari has suggested that reconnecting with supportive people is one way to fight depression. Australian social […]